The New Unnatural

Gean Moreno with Tami Katz-Freiman

Tomer Sapir, “Slide from Research for the Full Crypto-Taxidermical Index,” 2010-2012. Computer PPT played on a continuous loop. Courtesy of the artist and Chelouche Gallery for Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv.

GEAN MORENO (RAIL): Let’s begin with this idea of the unnatural. I think it is important that it marks a difference from the artificial. Artificial implies antithesis with the natural, while I think that unnatural, more unstably, alludes to something that scrambles from within the natural or nature as a convention that we have constructed. One thinks of Aziz + Cucher’s photographs of subcutaneous-phenomena-as-landscapes as unnatural, although it would be difficult to call it artificial.

TAMI KATZ -FREIMAN: The whole show plays with the gap between the unnatural and the artificial, because they are not exactly the same thing. There are works that are unnatural and works that are artificial, but all the works have something artificial, even if the result is unnatural. Artificiality is a basic strategy of the artists as a response to the artificiality of our lives, of nature, especially in Miami.

There is a paragraph in my introductory essay [in the catalogue] in which I specify the issue of why the show happens in Miami. It’s not by chance. One cannot imagine a more appropriate venue for this exhibition than Miami—which was built as a consequence of the large-scale draining of swamps into artificial lakes and canals. As a city in which nature has been processed to extraordinary degrees of synthetic cultivation, it is a site where the gap between the natural and the artificial has been completely blurred. Indeed, Miami may serve as a powerful parable for the unnatural. The palm trees on the golden oceanfront, the hibiscus flowers, the mangrove roots and the pastel palette of the Art Deco buildings may be thought of as a glamorous façade, a stage set centered on simulating an experience of paradise on earth. The presentation of UNNATURAL in Miami Beach—a subtropical, botanically lush barrier island that was built on a filled coral reef, and where even the beach sand was artificially imported—further strengthens the tangible relationship between “natural” and “unnatural.”

RAIL: It’s about a construction of territory, too. If one thinks of the number of Israeli artists in the exhibition, one begins to draw comparisons—Miami and Tel Aviv, for instance. One starts seeing how different constructed spaces can be; how, if enough of these constructed territories are placed side-by-side, one may have to give up the fantasy of some natural, neutral, “virgin” space.

KATZ -FREIMAN: Although I took it out, I began the catalogue essay with a very personal experience I had in Alaska last summer. With my daughter and my husband, we rented an RV and drove into nature. And I realized that, even going into the most wild of reserves, there is no such thing as nature. Everything is controlled, regulated. When this happened, I was already working on the show and this was a very revealing experience. It was the most natural nature I had ever been exposed to, and I realized that even there things are already constructed and controlled. Even the most remote stretch of wilderness, the frontier, is today managed, mediated, and domesticated.

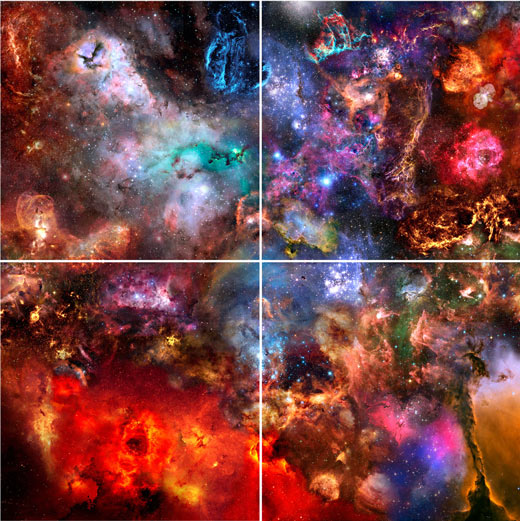

Boaz Aharonovitch, “Dark Matter” (2010-2012), four archival pigment prints,Courtesy of the artist and Dan Gallery for Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv.

KATZ -FREIMAN: Yes, that sounds very ‘90s—the post human discourse.

RAIL: Now it’s different. Swarm intelligence is applied to computing networks and things like that. Species and technologies and bodies are all leveled and information circulates between them. This is different from the shocked responses that saw the artificial as a violent intruder.

KATZ -FREIMAN: This is a good time for this show. There is something there. I deal with this in the catalogue essay through the notion of constructed landscape. Landscape is always already a construction. It is in our brains, in our culture, more than out there. You mentioned the Israeli artists in the show. How is their experience different from that of non-Israelis? In Israel, landscape has an extra element that aids in its construction: politics. Territory in Israel is so charged with the pending issue between Israelis and Palestinians. Every usage in Israel is charged, even before you add any input (right wing/left wing; conquering/not conquering). The fact that Israeli artists deal with this reality infuses their examination of nature with a political charge, while leading to a critical engagement with the concepts of territory and landscape. In the contemporary Israeli context, it is impossible to disassociate the landscape from its political resonances and from the multiple narratives that surround it. Landscape imagery and representations of nature in contemporary Israeli art are rarely ideologically innocent, and are certainly not romantic. They are scorched by the fire of conflict and marked by the fervor of internal controversy. This context, where territory itself and ownership over it are the source of a fundamental debate, clearly reveals how every act of representing nature is inevitably political and suffused with ideology.

RAIL: What increasingly complicates the division between natural and artificial is that everything is broken down into information that can be transferred. In the exhibition the majority of the works depend on a literal breakdown of images and objects into data, into digital files.

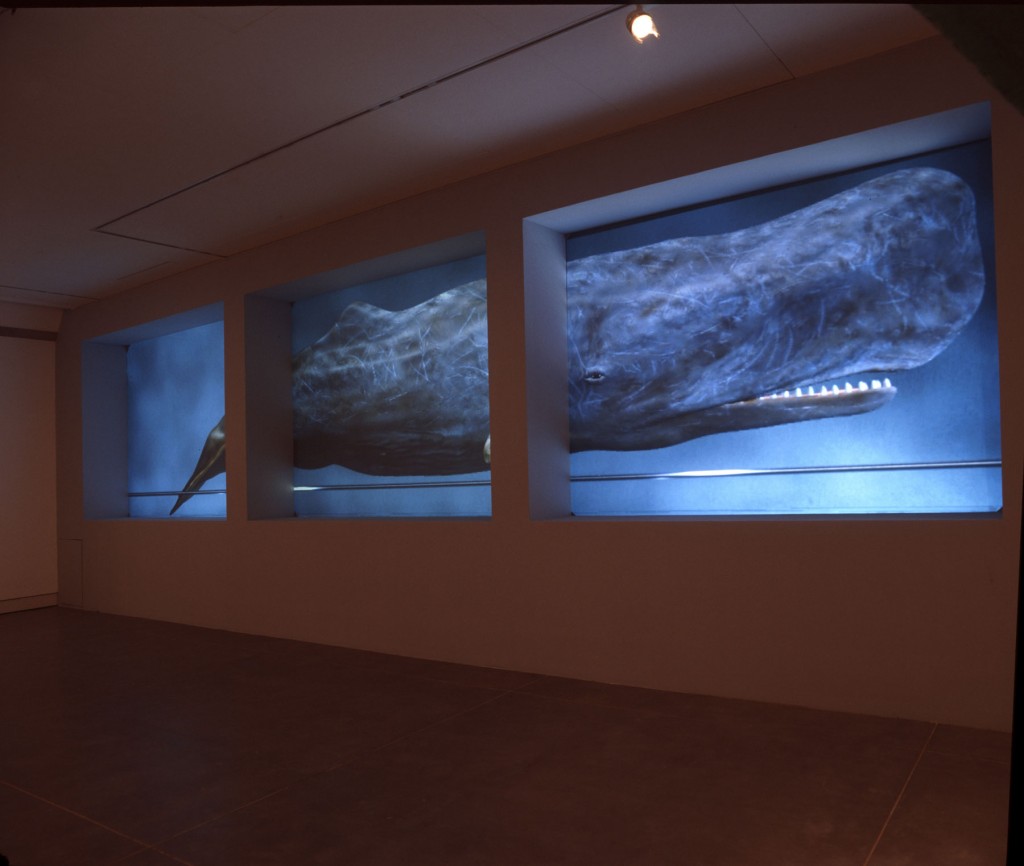

KATZ -FREIMAN: The mediation that was so important for photography does not exist anymore. Things are constructed. But there are some works in the show that use straight photography, such as Rose-Lynn Fisher’s microscopic photographs. Photographic practices still play a central role in representing nature, especially in terms of the range of manipulations they make possible. Photoshop, video, and scanning, alongside other digital technologies, enable artists to create deceptive simulations and synthetic forms of man-made nature. Samantha Salzinger creates imaginary topographies of a mysterious and imaginary natural world, which she represents in the form of dioramas. Boaz Aharonovitch’s supernovas were created out of countless Internet-based images. Ori Gersht’s works similarly challenge the perception of photography as a tool for reporting on reality. And Meirav Heiman and Yossi Ben Shoshan’s sperm whale brings to a climax the conflation of the organic and the digital, while entirely undermining the concept of the “natural.” This creature, whose body is an illusion composed of pixels, is the most virtual one in the exhibition.

In the catalogue essay, I explain this by creating different categories [through which to approach the works in the show]—the category of what we see (it includes landscapes, forests, animals, plants, flowers, etc.) and the category of photographic usage. I also explain through the idea of different approaches to nature—a scientific approach (in the works of Rose-Lynn Fisher, Tomer Sapir, Uri Shapira and Shachar Freddy Kislev); ecological and political approach (in the work of Blane De St. Croix and Tobias Madison); a romantic approach that deals with the 21 st century sublime (in the works of Gal Weinstein, Guy Zagursky and Yehudit Sasportas) and a poetic approach (as in the works of Sigalit Landau and Dana Levy).

RAIL: But the idea of the sublime is complicated by a world broken down into information. Think of Boaz Aharonovitch’s photographs of supernovas. Everything in the image should cause awe. The magnitude of what is captured, the force of exploding stars, the unfathomable cosmic distances that are suggested. And yet, as images procured through Google searches, the possibility of the sublime is difficult to save. This complicates the usage of our old categories and concepts.

KATZ -FREIMAN: Yes, they are not useful anymore. Now with the Higgs boson particle and things like that, there is some momentum there. The show is a reflection of this. There is a correlation. This is how artists are thinking through this. The contemporary discourse on nature is interdisciplinary and undermines traditional divisions between different fields of knowledge: studies in areas such as environmental ecology, ecoactivism, biotechnology, biomedia, botany and zoology, experimental geography and anthropology, alongside concepts such as extinction, biodiversity, and utopianism, have become an integral part of this artistic discourse.

RAIL: It goes back to what I was saying before. Cyperpunk, which was supposed to be a direct engagement with an encroaching technological and artificial sphere, increasingly reads as the opposite—a last-ditch effort to defend something. And now, it’s as if some collective acceptance that it’s all information, all the way down and all the way up, from DNA to the Milky Way, has come to pass. And once all is understood as information, the idea of transfer becomes easy to digest. All of a sudden, it’s easy to think that the process of plant growth can be applied to architecture, for instance. And this seems like it divests us of all the exhaustion that characterized the end of the last century.

KATZ -FREIMAN: Is this the true meaning of “new age?”

Meirav Heiman and Yossi Ben Shoshan, “Sperm Whale,” 2009, four-channel HD video installation, sound. Courtesy of the artists

KATZ -FREIMAN: You are absolutely right and this is also in Yehudit Sasportas’s forest video installation, as well as in the steel wool drawings of Gal Weinstein, in Aziz + Cucher, and also in Michal Shamir’s digital prints with the petals, which are three meters wide and so the petals are rather large. So there are many places in the show where this issue of scale can be approached. The whale, for example, is the most accurate piece in the show in terms of scale. It is literally life-sized. But we are not used to seeing this way in galleries and museums.

RAIL: I think that there is a need to problematize the antithetical structure that has been established between scale as a legitimate property of sculpture and size as some spectacular, intrusive, bad element that characterized the work produced for global museums. This binary feels too simple. I think it goes back to the need to reconsider whether human scale still needs to be the metric we use, the governing point of reference.

KATZ -FREIMAN: I didn’t think about this from this perspective, but it is very interesting how we’ve shifted away from a human scale. And I think it has to the do with a next step following the iconic shift in the ‘60s with Rauschenberg—the shift from the desire to represent nature to the desire to represent culture. If you think of the Modernist movement, the Impressionist, even the Futurists, the main motivation or drive was to represent nature, to represent reality. In the 1960s—Leo Steinberg proposes this in his analysis of Rauschenberg—there is a shift from representing nature to representing culture. When you represent culture you are working with images, with constructed images. This is the main revolution of the 20th century in culture—what we called Postmodernism. I’m fascinated by this, by what happened to the human mind after World War II and the way that artists reflected this in late 20th century art. UNNATURAL represents a third step after this shift to representing culture. It’s still dealing with culture, but with a very specific culture. It’s not what Pop Art did. We are dealing with the image of the image of the image of the image and the image is informational or information.