Christina Pettersson, The Castle Dismal

Hunter Braithwaite

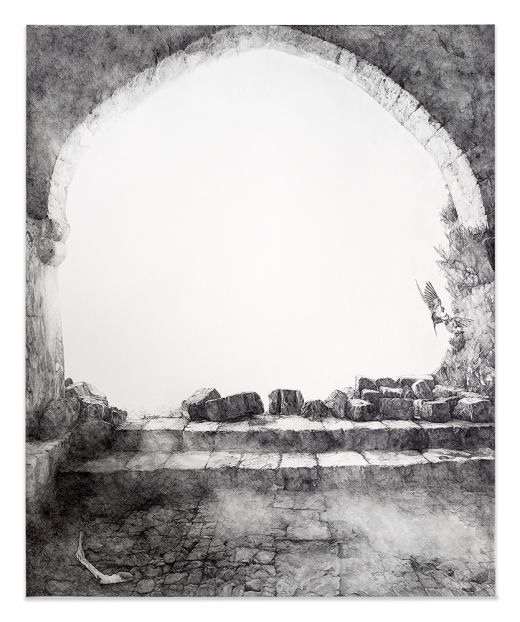

Christina Pettersson, Oh Lucius, This Ghastly Flooring, It Wounds Me So, 2013. Graphite on Paper. 58 x 72”

April 18 – June 20, 2014

The gallery has three drawings, with the largest, “The Terrible Knowing & Not Knowing” stretching across four sheets of paper to form a composition thirteen feet high and twenty-eight feet wide. It’s as large as a Hollywood backdrop. Think Gone with the Wind, Tara in flames. Tomorrow is another day. Except it’s not. All of the action that happened on this sweeping southern stage happened long ago.

The first thing one comes to is a charred funerary carriage—hand made by Pettersson. Burnt black and stripped except for tattered curtains, it is an uneasy memorial to Sherman’s seaward waltz.

Installation view of The Castle Dismal

The Castle Dismal is, like the literature and the place it channels, an amalgamation. It is Southern, sure, but the very name of the exhibition is not. It’s Nathaniel Hawthorne’s name for his childhood home. Hawthorne, a Romanticist, grew up in Massachusetts. But from a distance of a few hundred years, it all begins to feel the same, with elements of Poe and Faulkner cropping up as well. Pettersson is just working the material. Even before Robert Smith, the Gothic was a style of literature, of architecture, and the Germanic tribes who sacked Rome.

One has seen a lot of Gothic inspiration in contemporary art. Alongside the Germanic palpitations of Jonathan Meese, the methed-out pentagram dreams of Banks Violette, or even the Motor-City Frankensteins of Matthew Barney, there is the ornate breed of the Southern downfall. To this, Pettersson lays claim.

Like any good southern novel, Pettersson’s exhibition is a story of stories. One next encounters the monumental columns of the ruined Windsor plantation. Located on the banks of the Mississippi around Port Gibson, the mansion was built by one Smith Coffee Daniell II, a wealthy planter, former Indian fighter, and cousin betrother. When the mansion was completed in 1861, it was the most luxurious home in the Antebellum South. Greek Revival in style, the home was known for its 29 columns, each 45 feet tall, capped with Corinthian capitals. Mark Twain stayed in the house. Confederate soldiers stayed in the house, as did Yankees. In 1890, however, a stray cigarette or cigar (a detail which changes depending on how dandyish the rendition of the story) made its way to a pile of wood chips, and the whole thing burned right down to the delta dirt.

In the project room, which she has painted a clay-brown. Far from the door floats a model riverboat. Beneath it is a mass of melted candles and porcelain knickknacks forming a makeshift vigil to honor the dead of the SS Sultana disaster.

Another tale for the veranda: On April 27, 1865, a drastically overloaded steamboat with a boiler on the fritz pulled out of Vicksburg and exploded. Approximately 1,800 died, making it the worst maritime disaster in the nation’s history. That said, you probably haven’t heard of it, because it was completely overshadowed by the execution of John Wilkes Booth the day before. One of the boats which came to pull the few survivors from the icy Mississippi was the steamer Jenny Lind, named after the famous Swedish opera singer.

A wooden bust of Lind is found at the other end of the small gallery, cracked with age, but also mutilated by Pettersson. A thick spurt of pine tar erupts from a gash in her throat, and pools on the ground, surrounding an unfolded straight razor. It’s a maudlin bit of theater, the inclusion of the razor, because the thick, heady stench of the tar is more than enough to conjure a dark, violent past.

This show marks a tentative move into sculpture for Pettersson; I hope to see it explored with the dedication and bravado of her drawings. Exiting the dank parlor of the project room, back into the contemporary space of the main gallery, I want the walls to be papered and the drawings framed in gilded filigree. I’d like to see it all recreated, held in limbo in a “dim hot airless room with the blinds all closed and fastened” as Faulkner once put it. Like the Antebellum South, the room is too white.