The performance-artist duo’s work is well outside the typical realm of the safe and sensible, crossbreeding pirated Mexico City cumbia and Argentine disco with obscure musings of Pérez Prado and Miami Booty Bass. Eamon spun the soundtrack as DJ Lengua, while Julio ran the visuals: strange, often violent video trips projected onto a white screen and distorted with a Kaos Pad.

I was thinking of my life back in Guyana because I’ve just come back from there—this is me re-examining my past, thinking about what it was like to grow up in Guyana when the country became a socialist co-opera-tive republic. Being in Miami I am very conscious of the predicament of Cuban Americans in relation to the piece, “For Those in Peril on the Sea.” Last time I was here I took a cab ride and the driver had come over from Cuba and he was telling me how he got here.

On the verge of spring, two Miami museums opened shows that went past the normal role of the museum exhibition—that of the public face of the institution. Romans à clefs to the museums themselves, they gave coded insight into how new acquisitions, permanent collections, recent achievements, and aspirations for the future come together to create the institutions of today.

I am constantly on the search for people of my generation who are pushing forward —not irreverently but fearlessly. This describes Alex. He possesses a strong understanding of the past, a drive to explore the present and anticipation for the future. And so, the conversations between us began and continued. The below is a conversation from a lovely Monday morning in my office on Canal Street.

In the 1980s, Tyson was seen as both an animal and as a machine—the tenaciousness with which he trained, combined with the savage clockwork of his fights, produced a truly liminal man. Yet it was in the 1990s, when a series of controversies calcified to create a type of death mask of noble public figure. In other words—a celebrity. This extent of this evolution shown in the light of the screen, which featured his trademarked (this isn’t a figure of speech, ask the producers of The Hangover II) facial tattoo, looking like a decorative ninja knife mounted above some drug dealer’s flat screen.

Donald Chauncey has been a cultural mover and shaker in South Florida since you were in short pants. He was born in Clearwater, Florida and has spent most of his time in Miami as a film librarian and retired as director of a moving image archive. He relishes being labeled “Dade County’s official pornographer” by a local pastor protesting his series of banned films shown at a Miami-Dade Public Library.

BFI is in a warren-like, artist-run building on NE 11th street in Downtown Miami. Here are a few things you can see from the sidewalk: the color-saturated façade, its rich blooms of color marked here and there by delicate graffiti commentary; an exotic dancers club; various high-rises, some of them attended to by the city’s ubiquitous construction cranes; mostly empty parking lots, the asphalt fighting a losing battle with vegetation; a lot of down-and-out people, some of them apparently homeless, some of them apparently in the throes of addiction; big, gorgeous sky.

Where does a retrospective begin? Is it with the most recent piece in the show, as retrospection literally means to begin at the present moment and then retreat into the past, or does it begin with the earliest pieces—the scribbles and student work, those made before the artist hit his stride? Or, should one look through the pieces on display to find an exemplary work through which the entire career and life shines crystalline? When choosing a path to enter Arnold Mesches’s endlessly American oeuvre, one finds that the earliest work (1945) is an augury of all of the paintings to come, up until the last was picked up from the artist’s studio, still wet to the touch, in December 2012.

Since 2008, the wulf. has been one of the pre-eminent venues for experimental music in Los Angeles. It’s housed, along with its two founders and directors Eric KM Clark and Michael Winter, in a downtown loft, which means that attending performances is a close-knit affair: the audience sits on dining room chairs, or couches, or on the floor, and there’s always a bottle of whiskey and bags of snacks on a table next to the bowl for cash donations. The wulf. is both a space and a community.

It requires thousands of computers performing the same task to force a “take down,” footnoted in the exhibition’s press release as a “denial-of-service attack,” i.e, unavailable page. Yet, rather than an empty threat, the disintegration witnessed in the hallway was a partial re-staging of an artwork already present in the exhibition, “Anonymous vs Art” (2012-2013). A digital print on stretchers, the piece depicts screen shots as simple proof of successful momentary attacks performed against corporate art world websites, including tate.org.uk and davidzwirner.com.

The following conversation took place poolside at the Soho Beach House on Friday, April 19th. As LAXART Director Lauri Firstenberg and Miami Art Museum Chief Curator Tobias Ostrander spoke about Los Angeles, evolving audiences, and the viability of the non-profit model…

The navigability of a space is crucial to your experience in it. The way light enters and exits, how sound travels and how visitors are guided through all play into the functionality and aesthetics of a building designed around the sensory experience. The newly renamed and remodeled Emerson Dorsch Gallery’s co-owners and architectural collaborators clearly considered these factors and articulated a thoughtful, sleek new home inside the Wynwood warehouse they have occupied for over a decade.

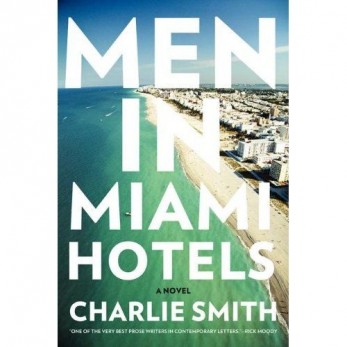

Charlie Smith has published seven novels and seven books of poems, has received countless awards, and has no Wikipedia page. If you Google him, you’re more likely to come across tales of another Charlie Smith—a man who claimed to be 137 years old when he died in 1979 (incidentally in central Florida). That Charlie Smith spent his later years telling his life story, all the while researchers tried to debunk it. This Charlie Smith is the 65-year-old author of the new novel Men in Miami Hotels, set primarily in Key West. In the early ‘90s, George Plimpton called him “a young William Faulkner.”

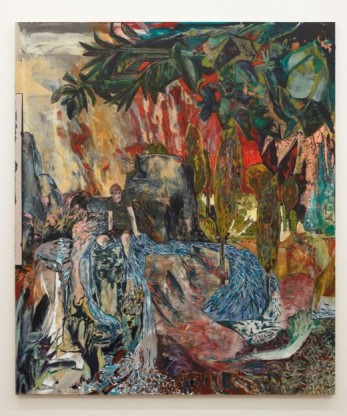

Hernan Bas has characters—boys. How he places these young men in their landscape is his conceptual project. A method of reusing and repurposing historical systems is devised to create a blueprint for the work, with identity politics, medium specificity, studio labor poetics, and market dependency all functioning as proof of its own language.

When I recite Hopkins, hydrogen, helium, lithium, beryllium bubble up instead of…

Artists have always had a funny relationship to this kind of neighborhood change. There is the way that they relate to the neighborhood’s history, their political practice, their values—these things seem to vary from case to case, with different stories coming out of San Francisco and SoHo, etc.. Miami has its own very peculiar history as a city, never mind who these artists are and who the people in Wynwood are.

It was a utopian scene. More than 80 folding chairs faced a chalkboard adorned with multihued verses as coworking campus The LAB Miami hosted a Friday night poetry and ballet commission as part of the O, Miami Poetry Festival. Tables of complimentary wine and desserts flanked Minerva Cueva’s égalité mural, a defaced Evian ad profiling the archetypal French revolutionary adage, the peer-progressive slant of which mirrors The LAB’s goal: to provide an urban home for a very mobile creative class.

A range of factors explain the ebbs and flow of attendance at art museums. General interest exhibits or renowned artworks on display can generate enthusiasm,but perhaps one of the most exciting events is the unveiling of a new museum itself. On April 13, 2013, following 10 grueling years of unpredictable delays, the Rijksmuseum opened its doors to an anxious crowd of nearly 20,000 visitors.

Fly into Dubai and even post-recession 2008 the glitz and the gold are still there as billed. The red-bull energy that shot up the tallest building in the world, an all-missions-possible airport, and a mall that has made shopping a natural resource, is still filling five-star hotels, stocking three-star restaurants and erecting corporate verticals.

A quarter-century ago, Joan Didion wrote about the peculiarity and the warp of Miami, describing what we, as Miamians, find unique and amazing, yet sometimes ugly and despicable about our city. Much has changed since she published that line in 1987, but the peculiarity and the warp are still here, and O, Miami was here to remind us.