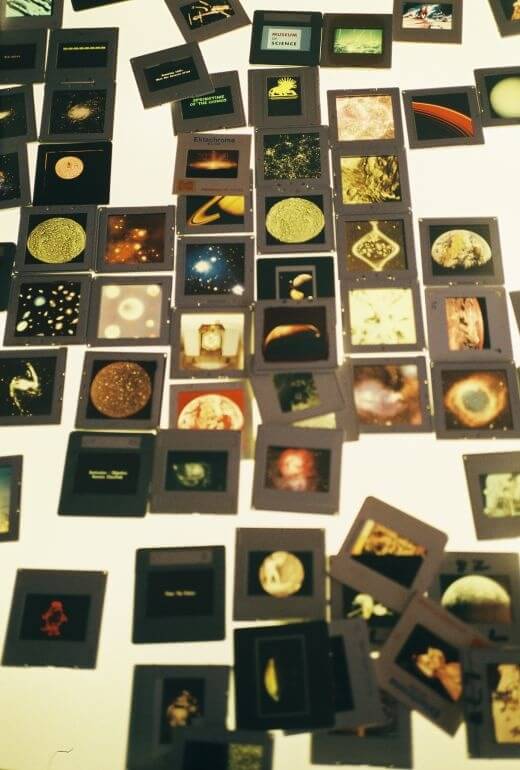

This—aging, vinegared history—is what it smelled like on an exceptionally sticky day in July at the headquarters of Obsolete Media Miami (O.M.M.) in the Design District, where O.M.M. cofounder, preservationist, and film archivist Barron Sherer was disposing of the culprit. (Vinegar syndrome, he explained, is contagious—to other rolls of film.) But it was not unpleasant; in fact, given the archive’s interior life, it was a little bit intoxicating. The sun was streaming inside and a NASA documentary screened on a projector while Kevin Arrow—artist, collector, art and collections manager at the Patricia and Phillip Frost Museum of Science, and O.M.M.’s other half—projected overlaying visuals, creating a living, moving collage. Though O.M.M.’s space is wide open, it is crammed with old slides, archived footage, vintage equipment, and found art, all organized tightly enough to feel streamlined but nonchalantly enough to recall an especially fun attic. It is all meant for perusing, browsing, and, for some visitors, utilization.

This is happening in a rather literal sense through actual media transfer, but also more holistically through artistic collaboration. David Brieske, Richard Vergez, and Dim Past are a few musicians currently working with sounds found in the archive for new recordings; pop-up film screenings of archival material are planned throughout the Design District.

At the Miami International Airport, O.M.M., commissioned by Yolanda Sanchez—who manages the fine arts and cultural affairs division of the Miami-Dade aviation department—created a roving pop-up cinema in the concourse, featuring silent films and creating, as Arrow explains, “an antidote to Fox News and airport TV.”

That’s the essence of O.M.M.’s community presence: giving back by getting others involved. “Our careers have always been about public service, so now these artistic practices are lining up with that,” says Sherer. “It turns out all these nutty, DIY tactics we’ve used have value.” In June, as part of Locust Projects’ LAB (Locust Art Builders) program, a class of local high school students visited the archives and made prints using old slides and images; Sherer and Arrow are putting together a filmmaking workshop, featuring Super 8s gifted by the artist Julie Kahn. “When the kids from Locust came by, they started using Photoshop terminology without even realizing it,” says Arrow. “Instead of sandwiching the slides, they were making layers. Instead of hole-punching, they were deleting.” Hobbies are satisfying conduits for any particular interest—they allow room for constant growth and sometimes act as a medium themselves—but they are much better when they become less singular, more communicative. O.M.M. is satisfying for geeks and inspiring for artists, but it’s also a real educational resource, hosting classes and allowing others to explore, rent, or somehow incorporate parts of the archive into their own work.

Adds Sherer: “It’s a post-Internet thing: you realize that people have the same interests that we do. Just sitting in your garage with your slides and film is one thing. Then you realize there’s this interest everywhere else.”

Monica Uszerowicz is a writer and photographer in Miami.