Tracey Emin, You Loved me like a Distant Star. 147.3 x 165.1 cm (57.99 x 65 inches) Neon [Pink Heart, Super Turquoise Text] 2012. Copyright the artist. Courtesy Lehmann Maupin, New York and White Cube, London.

Tracey Emin’s career and life are inextricably conjoined. Her installations, sculptures, drawings and notorious neons from the last two decades are unmediated, honest accounts of her own life. Writing, in many forms, is central to her work and often appears as her own handwriting, the immediacy of which is captured and made permanent in her neons. These are the focus of her solo exhibition Angel Without You (December 4,2013 – March 9, 2014) at the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami. The exhibition, her first solo museum show in the United States, is a concise collection of work that zeros in on the bare, glowing writing and allows a rumination on the core dialog of her work without the complications that come with earlier pieces like “Everyone I have Ever Slept With 1963-95” (1995) or “My Bed” (1998). Her explicit, open-book approach to art-making has been met with both high honors and ugly criticism. But though her work encompasses very personal and traumatic experiences, it extends beyond just a public exploration of the intimate self. The communications in these works—the dangling sentiments that can be lonely, aggressive, vulgar, trite, beautiful or funny—speak frankly of the more general human experience. Identity is not fixed but exists on a continuum, and her work reflects this ever-shifting nature of a person’s life, and all of the gritty parts in between.

Though it might not be immediately apparent, the often-frenetic, diaristic writings, wrought with childlike misspellings and grammatical peculiarities, are raw but carefully selected scrawls. Pulled from an endlessly streaming personal narrative, the neon phrases are what she chooses to broadcast and make permanent. These candid frozen snippets are the traces that will speak as her legacy. “I’ve always written,” she relayed to me in a brief interview, “and at one time when I was much younger I thought that there was a much greater chance of me being a writer than an artist as somehow what I write seems more sophisticated than my art, but my primary work is visual… Sometimes the happiest that I am in my life is when I am reading.” Reading and writing for Emin are constants, and are as vital to her art-making as the construction of any object.

Let’s pare this down and talk about words and identity. In viewing and reading about Emin’s work you might encounter such words as cunt, slut and its British equivalent slag. And, perhaps as a result, feminist. Words like these elicit an instant response that tends to shunt them into two approximate ruts: the artist wields power by shock or subjugation, or the artist must be reclaiming them as feminist. This might seem like a simplistic polarity I’m postulating. It is. It is problematic on several levels. For one, it assumes that the work fits into one of these two boxes, and for another it imposes rather rigid limitations all around. In regards to Tracey Emin, a couple of related and curious complications arise. She has noted that while she identifies as a feminist, she does not as a feminist artist. But certainly the response to a female making work with overt sexual expression can prove to be quite different than it is to a male making work of the same nature. Emin hardly invented pornographic scribbles and crudely written uncouth phrases, or explicit sexuality in art for that matter, just as she didn’t invent using neon for art. What, then, can account for the discrepancy in how her work has been received over time compared to her contemporaries—female and (mostly) male? Her response when asked about this distinction is interesting:

There [are] still women being burnt to death. Just because western society has changed doesn’t mean that other parts of the world have. We are still living the time of the witch- hunt. If I was in England in the 16th century I know for a fact that I’d either be burnt or drowned. I think there is still a great amount of inequality in the workplace for women regardless of the type of occupation—whether [you are in] art or a CEO of a big company.

Emin defers the term feminism as it relates to her artwork—she seems to not want her darkest personal experiences that she has openly described both in her work and in interviews to beg comparison to the plight of women still suffering the horrific contemporary iterations of archaic repression. While it could be said she has been burned at the stake (male critics have been particularly harsh) and otherwise victimized, I don’t think that she intends for her work to be about being a victim, a martyr, or a shock artist. I also do not think she is a feminist artist insofar as she intends to use her sexual exploits or body as a statement for female advancement or sexual autonomy.

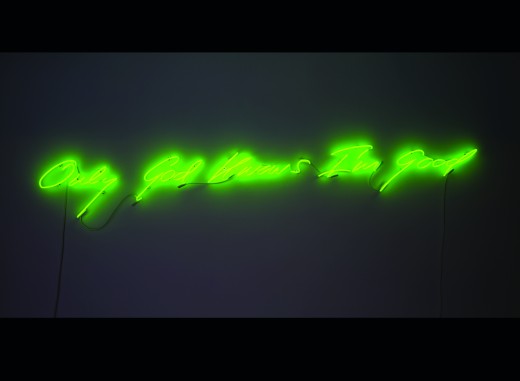

Tracey Emin, Only God Knows I’m Good, 2009. 20 x 117.21 inches. Courtesy the artist and White Cube, London and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong

So what is it about Tracey Emin that has made many males so uneasy? Is this dogged and confrontationally revealing approach not what is expected from sexualized females? You don’t have to like her work, or feel that it deserves the accolades it has incurred to detect the unbalanced response to it; think of how something like Vito Acconci’s “Seedbed” (1972) might be discussed in comparison to “My Bed.” I can imagine her work might feel a bit alienating to male viewers, but things like sex and masturbation are the most basic common experiences for both genders. It’s the more unpleasant over-shares that seem to get an adverse reaction from men—topics such as abortion or rape. Perhaps men feel uncomfortably implicated? It would be silly to say that every man who is critical of her work is sexist. It’s equally dubious to, as Sewell does, dismiss it as something that intrinsically men can’t understand from a firsthand perspective and therefore don’t care about. That doesn’t afford either gender much credit. Maybe it’s that she appropriated the nasty insults first. Words like “Fuck off and die you slag ” merely make those who were already thinking them reflect on themselves for harboring such thoughts. Interestingly, earlier in his review Sewell calls Emin a “drunken slut.” Or maybe it’s just that the sentiments in her work conveying frustration, desperation, loneliness and loathing feel too real and uncomfortably public—Emin just pulled them out of the closet.

But much of this describes the Tracey Emin of many years past. Given that her life is her source material, is it still viable for her to make work about something she is no longer living? It means now she is able to make her work at a certain level of remove, though its effect appears much the same. It is uncertain, though, whether current critics have acknowledged that there was Tracey Emin then, with all her messy confessionals, and there is Tracey Emin now. Is it fair to call her a drunken slut if she no longer drinks and is celibate? People shift and life changes. Who is Tracey Emin today?

When I last installed “My Bed” in an exhibition in Frankfurt last year it had been five years since I had last seen it, and all the artifacts that go with it. When I arrived at the museum there were all [these] trestle tables with small plastic bags… it looked like the forensic scene of a crime with all the evidence before me. As I started to install the piece I realized how much my life has changed since its first conception in 1998. I don’t drink spirits, I don’t smoke cigarettes, I don’t have partners who smoke marijuana, I am now celibate so I don’t use condoms or the contraception pill, I don’t have periods and I certainly don’t wear sexy underwear. The bed is 1998—it is like a time capsule of my life so when I install the bed every- thing is like touching a ghost of my past. It’s not so much redundant but more melancholy.