The Evolving Alternative

Westen Charles, Matthew Higgs, Rene Morales, and Gean Moreno

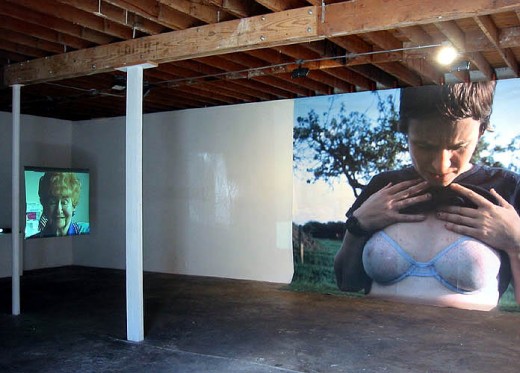

Installation view: Ruben Ochoa, "Cores & Cutouts," held at Locust Projects November 12, 2011-January 28, 2012. Photo courtesy of Ginger Photography and Locust Projects

RENE MORALES: Okay, well I’ll start by mentioning that we are currently sitting at Locust Projects—Matthew, I don’t

know if you’re familiar with this institution?

MATTHEW HIGGS: I am, yeah.

MORALES: It was artist-initiated, for a time artist-organized and artist-run. For how long, Wes?

WESTEN CHARLES: It was three or four years, at that point we financed it ourselves.

MORALES: And that was you, Wes?

CHARLES: Myself, Cooper, and Elizabeth Withstandley started it.

MORALES: And Gean, you participated pretty early on in certain things, right?

GEAN MORENO: I came on in 2002. I organized the exhibitions for a while.

MORALES: It was located in a different space, and then it got kind of kicked around into different spaces—it has now ended up in a pretty large space, and in the process it’s really moved from an informal artist-initiated kind of venue into a place with a director and a board, fundraisers, etc. It’s interesting to talk about this topic in a place that has really gone through this evolution.

CHARLES: Today we have grown to a point where the organization is much larger and deals with a lot more dailies. One of the things that we’ve been wrestling with is trying to maintain the feeling of the early shows. In the beginning years, the art was spontaneous by necessity. It was made in the space, it was something that had a real energy. Today, when you’re planning shows, sometimes years in advance, they seem to face an issue of being influenced by

the structure of a more established exhibition space.

HIGGS: Can I ask something? How did the arrival of Art Basel in Miami Beach and the far more visitors in Miami engaging in the contemporary arts have an impact on an organization like Locust Projects at that time?

MORENO: Well, I don’t think it was as big a change as it may be imagined from the outside. What it allowed was the possibility of working with artists with a little higher profiles. But I think in general at that point and for the next four or five years Locust was still about creating bridges between local artists and someone coming from the outside. And I think that went away when the Warhol Foundation started funding Locust, and certain structural and administrative rearrangements happened. Things were formalized, and this was the moment of change, rather than Basel.

CHARLES: When we were putting together our shows at that time, we were pretty naïve about the art world. We didn’t specifically have an opening night for Basel, but we just had a normal show that opened actually on that same weekend. We were pretty lucky, because our opening night coincidentally was scheduled for Art Basel’s night out for gallery openings. And so we had a ton of people out to see the show, and it could have been very easily that we had done it on a different day, and nobody would have come. So, in the beginning we knew Basel was there, but we didn’t particularly know how to connect into it. I think it was a learning curve through the next few Basels, to try to figure out how to know how to catch the wave. Whether you jump into it, or wait for the right timing.

Installation view: Valerie Hegarty, Break-Through Miami, held at Locust Projects September 11-October 16, 2010.

MORALES: I think a lot of us feel that way, in other institutions here, too.

MORENO: But I find that this instant interest didn’t essentially change what the exhibitions were about. When large funders came in and, reasonably, demanded changes to go with the money they were giving—that’s when the institution morphed into something much more formal.

MORALES: Basel is a factor that can’t be discounted. It gives you a kind of leverage, so that, as you said, you can bring in more high-profile people, if that’s what you’re interested in doing. People you wouldn’t normally be able to work with, if we were, you know, in Wisconsin somewhere. On the other hand, there’s always the risk that that same leverage can distort your mission and your program, where you start programming a certain way because you have that leverage.

HIGGS: How did that impact the dynamics locally in terms of the space originally being conceived as an artist-run space, just like White Columns was in 1970?

CHARLES: We had to embrace the idea of the change once the Andy Warhol Foundation took interest in what we were doing and wanted to support us. We worked with an independent advisor and went through all of our operations in order identify where we could be doing things better. One of the things that I gained out of this process was learning to embrace the old analogy that the individuals that build a ship aren’t necessarily always the captains. In the beginning, most of the public connection to the organization was through the founders, and it was a very personal connection. Supporters were interested in the art, but there was always a direct connection to a person. During our first transition period, the goal was to take the focus off any individuals and have our mission be the real identity of what we were doing, rather than any person. So that if something was to change with a particular person at Locust, it wouldn’t effect what we do.

MORENO: I think there was this progressive distancing. Maybe it didn’t manifest itself immediately, but you could see as the years went by that there emerged an increasing disconnection between a kind of organic community and Locust as an institution.

CHARLES: But isn’t that just growth? I mean, if you stay the same, then I don’t think you’re doing your job.

HIGGS: In that case, Gean, was there a reaction locally where artists started other spaces beyond Locust, or other projects?

MORENO: Yeah, places have cropped up.

MORALES: I would say there are actually a remarkable number of artist-organized, artist-initiated spaces now, and it’s for complex reasons. Part of it is that Locust changed into this other type of institution, in a way creating space for new ones to crop up. But mainly it just has to do with really material explanations, like the fact that almost all of the art collectors here in town are also real estate investors. So therefore, a lot of people in the art world have access to spaces that they could borrow. In some cases those have led to one-night exhibitions. In some cases, those have actually congealed into venues, like Dimensions Variable or General Practice. Bas Fisher is interesting because it’s earliest.

MORENO:I was trying to say that as Locust formalized, it started to feel distanced from an organic, local art community. And this generated the need for these new spaces to crop up.

CHARLES: Well, what were the tenets of those early spaces, besides art and beer?

CONSENSUS: [Laughter] That seems to be the mission right there.

MORENO: That’s not true. Beyond the beer and the art there’s also this idea of community, this idea that you go there and you feel like you’re in a place that is yours, and that you are actively participating in a dialogue with your peers, as opposed to you going to visit a space like this.

CHARLES: Yeah, I’ll give you that.

MORALES: I just want to reiterate that the early phase of Locust, before it went through this formalization process, was artist-organized, artist-run. The projects were all artist-initiated. In other words, the local artist community was participating in the program of the venue. That’s something important that has ebbed as Locust has become more formalized. What I’m getting at is the question of whether it’s desirable and whether it’s possible to regain that degree of participation by the local artist community in the program of Locust now that it’s more formalized. I think that there are ways to do it, interesting kinds of experiments that you could do.

MORENO: But there were also a series of contingent factors. At the beginning, there was an apartment, a really shitty apartment, inside the space. There was no money for car rentals, so basically when artists came to work they were inside our lives. If there was a party we were going to, that’s where they were going. They just became grafted into your world and to the local scene. And so if you were going to play poker at someone’s house, he or she was going to go play poker, too. That was not a formal-artworld-dinner-with-a-board-member kind of thing.

RAIL: Maybe we could talk to you, Matthew, and maybe draw some parallels based on what you’ve heard about Locust Projects and Miami with White Columns, and then maybe we can segue into bigger-picture?

HIGGS: Sure. White Columns was founded in 1970 by Jeffrey Lew, who actually lives in Miami. It was very much a local space for local artists creating a context for themselves and their ideas. When the NEA came to White Columns in 1974 I think, it was at that point Lew lost interest in the space because it became too formal, and it became something else. White Columns was no longer a local center, I think it started to become a national center. Shortly after, spaces like The Kitchen started, Artists Space and so on, MoMA PS1 in ‘76. But the organization did change, and it this really had to do with having to become a bureaucracy. I think those kinds of changes are quite common to these organizations. It’s very uncommon I think for them to remain independent and to remain autonomous and to remain artist-run. I was involved with Cubitt in London and Cubitt was exactly the same. It was run by a group of friends who were artists and then it became a formally supported space. I think my relationship with White Columns is thinking about this idea of local, national, and international, and how you can retain or create an idiosyncratic platform for all kinds of visual culture that is distinct from what’s on offer at the commercial galleries and in the institutions. But also, and I think most importantly, is distinct from what’s on offer at the other non-profits. That’s what we’ve been working on here in the last seven years. Certainly you have various times at White Columns beginning in the late ‘70s, around the time of the East Village art scene, then in the early to mid-‘90s at the time of the Soho art boom, and again in the 1990s, when the directors of White Columns are on the record book saying maybe there’s no need for White Columns anymore, because there’s a really healthy art world out there. There are lots of opportunities for artists, and there are tons of great galleries. And for me that’s the interesting problem for us. I started here in 2004, the world’s economy was booming, the art world was booming, the Lower East Side scene was starting in New York, the Brooklyn scene was still there. It’s trying to find a reason to exist, and then trying to create your own territory, and then not defending it, just trying to amplify it. I think what one of the things I’ve tried to do is—because I’m not from New York, I’m not invested in the idea of New York as all the previous directors were, who were all from the City—is just to think a little more loosely about what it is this space can do and how we can do it. So, I’m curious about you know the investment in the idea of Miami—it’s obviously where you guys live and work. Is there a kind of investment in the idea of Miami?

Installation view: Synesthetics, curated by Felice Grodin, held at Locust Projects March 8–April 26, 2008. Photo courtesy of Locust Projects. Mural: Ed Young, Sculpture: Graftworks/MoB with Aaron White

MORENO: Matthew, do you mean each of us individually, or you mean in terms of the institution?

HIGGS: Well I think, for example, the first 20 years of White Columns are really a New York story, and then that story starts to get less certain in the third decade and now it’s completely uncertain in its fourth decade, even though we’re based in New York. So, that idea of locality was very important for this organization for the first 20 years, but it’s less so now. And my feeling is that, in Miami, that sense of locality is still more present as a conversation amongst artists locally, but just also in terms of how the organization thinks.

MORENO: It’s almost in Locust’s DNA to be Miami-centric, or at least that is how it still seems. There’s still the drive of everyone who was here at the beginning and is still involved, and then you wonder how that relates to new people who are coming in with different investments. That’s one of the tensions in the space now. It also started at a moment when the first generation of Miami artists as a group, self-identified and institutionally- and media-branded that way, came together. Locust opens at this moment and is rooted in this in some way.

HIGGS: I think you also saw this in the Bay Area, you know, the classic Bay Area not-for-profits, New Langton Arts, Southern Exposures, they’re almost exclusively local, almost as a kind of ideological, almost political perspective. Obviously that changed, too, as time evolved, but they really created a narrative art boom used in Northern California around their programs, and I think that sense of space or specific locality is still a thing in Miami, from my experience as a visitor.

MORENO: I want to amend what I said before because the programming was always bound to linking it up to things outside. If you think of the early exhibitions at Locust, they would put someone local in contact with folks from elsewhere. Although the institution itself was very rooted, it was also from the beginning really interested in drawing connections beyond the city.

HIGGS: And in that respect it’s quite close to the artist-run spaces in Glasgow, that by default of being away from the metropolis, London, started to create conversations.

MORENO: Yeah. I think it’s a two-sided answer. One side is that internally, at the DNA level, it was very Miami-grounded, but there was always a vision to link up to other situations and places, whether it was trying to deal with the guys at General Store in Milwaukee, whether it was bringing Mark Leckey or Eric Wesley.

Installation view: Phil Collins, New Projects, 2002. Photo courtesy of Locust Projects.

MORALES: I don’t think it’s actually possible to generalize a sense of Miami as being particularly locally oriented, compared to other places. In fact if you take into consideration the local collection spaces, the Rubells, the de la Cruz Collection— even though Rosa [de la Cruz] has her own little room for local production—what you see in these collection spaces is work from all over, Sterling Ruby, etc. And you could probably say the same for most of the institutions; although certainly MoCA and MAM in particular have always emphasized support for the local artist community and organized local surveys and included local artists in group shows that included artists from all over. So I think that there’s actually a balance right now. Now, when you were describing the Bay Area venues, you mentioned the ideological or political impulse to stress the local, right? I feel that one should leave that behind. At the same time, though, I do think it’s interesting to ask the question: what can you achieve through locality? What can you do by engaging the local artist community that you can’t do when you’re putting together a show of artists all over the place? I think one thing you can do is achieve a level of collaboration that you can’t if you have artists from all over the place, because you have access to the artists over a long period of time. You can increase the intimacy and intensity of the planning. Another thing is that you have an enhanced opportunity to work on projects that take place out in the city or that are about the city, because you’re working with artists who have a relatively strong familiarity with the place. Let’s say you bring an artist from elsewhere to do a project about this city, or located somewhere out in the city. Gean and I have talked about this; there’s often this helicoptering-in effect, and the product can sometimes feel a little glossy. You know, when you’re working with artists from here, at least in theory, they have the ability to penetrate more deeply into the city as subject matter. So those are just a couple of things I think that justify, if one needs justification, a locally oriented way of working.

CHARLES: Can I ask you a question? One of the things that I found that changed was the dynamic between the artist community and the museums. I remember before we started Locust, there was this “one way only” distance between the big museums and the local artists community. It seemed that when we started there was more of a middle ground and then it seemed that the museums kind of picked up on what we were doing and the energy it created and after that, you saw more museum people come to the shows and then the next thing you know the big museums are doing group shows with lesser known Miami artists.

MORENO: But you can’t give all the credit for that to Locust.

CHARLES: No, no, I’m not talking about Locust specifically, I’m talking about alternative spaces in general. I remember when there was a distance between the artist community and the museum, and from what I had seen, alternative spaces became a bridge of sorts, that brought artists and the museums closer.

MORALES: I’m not sure what accounts for it, but I agree that distance has closed a bit. It can easily open again, though.

CHARLES: I mean, why would directors of museums come out to these little places?

MORENO: I think we need to be careful. Since Locust survived a particular moment that other spaces didn’t, and other people who were there are no longer around, it can’t then take credit for everything. Because this is not the only space. I mean, this is a really significant and exciting one, but there were other spaces at one point, and there’s a lot of people who are no longer participating, who were there. I think we need to be cautious not to now pretend to be the messiah that changed the world, because that’s not fair to the entire community that worked together.

HIGGS: Moving things into the present, how would you describe the role of not-for-profit organizations in Miami within the larger context in Miami of these amazing private collections, the new museum that’s going up on the waterfront, and the few commercial galleries that are down there. I mean, 10 years on, where do you find yourselves now and how do you move forward?

MORENO: Well I would say we’re in suspended animation. I’m sure Rene has a different perspective on this, but we don’t know what the museum institutions are going to do at this point. They’re still being built and they’re going through changes. I think MoCA might be doing that, too, on a different scale. I don’t find that the commercial gallery structure is exciting at the moment.

MORALES: That really hasn’t been developing on the same scale as either the institutions or artist-run venues like this one.

MORENO: I also think that there are these artificially inserted things, right? So there’s this kind of street art thing here now, that is very liked, supposedly, and very well supported, that to me seems…

MORALES: Right, in fact hundreds of new galleries have emerged since I’ve been here but I’m still thinking of the same number. Some have closed and some have opened, but I think we still have what, like seven or eight?

MORENO: One of the big problems of this city is its lack of educational institutions that constantly insert new artists and energy and ideas into the scene.

CHARLES: A lot of our kids go away to college and then, well, a lot of them don’t come back. We don’t have a constant feed. We have New World School of the Arts, but I don’t know if that’s enough.

MORENO: I don’t know what the answer is to where either Locust is going to be in 10 years or where Miami is going to be, but I do feel that it’s not a terribly auspicious moment for art production in general in the city.

HIGGS: At the time we show something, it’s our belief that nobody else in the city would show that material at that time. And that seems to be an important way for us to think about how we program what we’re looking at. It also allows us to stop looking at other things and to think about, you know, information as perhaps not being privileged here. Historically, spaces like White Columns have been thought of us a kind of like a farm team to the major leagues, that an artist might show in a space like this and then eventually get representation or their work would find a bigger audience. That certainly doesn’t interest me. My belief is that these spaces historically and hopefully going forward are the most important spaces. They’re more important than the museums and they’re more important than the commercial galleries. In New York, the institutional sector is so established and in many ways extraordinary. The commercial sector is so large, and also in many ways extraordinary. There is a huge space between those two ideas, in which The Kitchen, Artists Space, White Columns, Printed Matter, you know, a dozen or more others, can operate. But for me it seems, we can’t wind the clock back to the glory days of this organization. New York isn’t the same city anymore. But I think we can behave differently and we can be independent and we can present things idiosyncratically. If we provide an alternative, it’s just an alternative to each other. It’s no longer a sort of them and us situation. But I got the impression, Gean, from some of the things you said, that there are some divisions still in Miami between the institutional framework and the kind of context that artists are working in independently.

MORENO: There have been certain crossovers and points of contact, but this landscape that you describe with an entrenched institutional world and an entrenched commercial world that create a middle ground where places like White Columns can maneuver—I don’t think that we have this landscape here. It’s not fixed like that. And so I’m not sure it would make sense for Locust or any other space to try to insert itself in an in-between space like that.

CHARLES: And when you have these personal collections that almost serve the role of the museums. The museums are young here; they don’t have the history of the collections that you kind of need in some cases to set a pace. So I think we’re just still a really young city and trying to figure it out.

MORALES: Something that I find interesting in this kind of situation is the question of how museums put on exhibitions differently from how the collectors tend to put on exhibitions. I don’t think there are inherent differences, you know. A museum could do a very collector-like show and vice-versa, there’s no reason why not. But there is a tendency to be more or less narrative. And then I want to go back to a point that I sort of hit on a couple times, partly because I’m organizing a local show that does very much ask these questions. I’m really interested in how an artist-organized exhibition tends to manifest itself differently from both the museum-organized exhibition and from a collector-organized exhibition.

And this ties in to something that Matthew mentioned earlier, which is that certainly, for a place like Locust, just as with White Columns, it makes no sense to try to relive the glory days of the institution. At the same time, though, I think you can ask the question of how Locust can integrate the participation of local artists more. Like for example, inviting local artists to organize exhibitions here at Locust, something as simple as that. And not just the exhibitions but the programs, you can ask artists to at least participate in developing the schedule of lectures, etc., etc.

HIGGS: I think in a way this is why the Bay Area spaces in the ‘70s, ‘80s, and beyond were very successful. They created a context for local artists to sustain their practice whilst living in the Bay Area. You can also argue that that became a problem, that it became a kind of closed context that allowed that work to exist and thrive in the Bay Area and never really find a way out of that context, too. So this sort of balance between local, national, and beyond, I think is quite complicated. But it’s still a relatively recent phenomenon in Miami. 15 years isn’t that long for a situation and a scene to fully unravel and develop itself. I mean you’re probably really looking at 20, 30, 40 years.

CHARLES: Matthew, has anything jumped out in particular that you have picked up on with regard to Locust’s challenge to handle continued growth and to maintain an identity?

HIGGS: I always think that the goal is to make the idea bigger, not the physical reality or the budget. We just take the lead from artists, and for the first time in a long time in its history, White Columns is run by an artist again. This is an artist-centered, artist-centric, artist-run organization, and we take all our leads from artists. And I think when some of these spaces do become more bureaucratized, the reason these spaces began starts to drift into the background. And it’s like how do you put the artist back in front of the picture? That’s the only reason these organizations exist, and it’s the only reason they really should exist, unless they want to become something else. A good example is the New Museum, which chose to be a different kind of institution. And I think they did quite brilliantly, because New York needed a space like the New Museum, like a Kunsthalle or Kunsthalle-type situation, which didn’t exist until that point in New York City.

MORALES: I agree. One of the things about artist-organized or artist-centric venues is that there is a relative amount of disregard for the kinds of conventions and self-imposed limitations that curators might be working with at a more formal place. And that can be really productive. The question is whether a place like Locust or a place like White Columns can harness some of that spirit, and how you can do it, even though you’re not an artist-run place anymore, you’re not what it was, you know, in 1970.

CHARLES: Do you find that trying to pay for what you do sometimes hampers how you do things?

HIGGS: We’re fortunate in that we work in a city where philanthropy for these kinds of organizations is pretty established. You kind of rely on that philanthropy. We’ve had to have much more imaginative ideas of how we finance and support what we do here, and a lot of the support financially comes through artists: through artists contributing to benefits, through editions, through White Columns having an interest in the commercial sector, and how we can participate in that to the advantage of artists. How we can create economies for artists, is something that we’ve really been developing for eight years, and I think during that eight years we’ve raised a couple of million dollars for artists. But my absolute belief is if you do interesting work, people support it. And I think there were times in this organization’s history that it wasn’t doing such interesting work, and the organization struggled financially. It’s important that I feel like every year is our last year at White Columns, just so that we keep understanding that we’ve got to raise our own game, in order to rationalize what we’re trying to do in the first place, which is to create opportunities for artists. If we’re not doing that, I don’t think we’re doing our job.