Nathlie Provosty, Doubleu (Dark), 2013. Oil on linen in two parts. 84 x 92”. Courtesy of the artist.

For the past few years, Provosty’s most successful paintings have been developing several formal devices, and in her latest works she has pared these down to arrive at a more complete realization of two of the most significant of these devices. The first is a juxtaposition of matte and glossy passages that variously reject, capture, and reflect light as well as the painting’s surroundings. The second is an attention to the edge of the painted field, where Provosty places subtle passages that pinch and curve pictorial space such that there is a general sense, on the part of the viewer, that the space is turning either clockwise or counterclockwise, at different rates and with varying intensity depending on the way Provosty handles these compositional elements.

In “Doubleu (Dark)” two sweeping passages of glossy black dominate the twin canvases, truncated by the slight separation between the panels; rather than simply echoing one another, they move in harmony with each other or continue where the other leaves off. The relationship is at once more intimate and more expansive than either term suggests. “Black” is similarly not quite the right word for the color, which is in fact a green that has been muted and muddied such that it has been dialed down to a very low pitch. Provosty built up many layers of green paint until she had a color approaching, but standing just to the other side of becoming, black. In different light conditions the painting becomes either darker and more reticent, or begins to glow as the painting’s green origins are revealed and suffuse its surface.

Two aspects of the painting, already suggested, are especially compelling. First, there are the glossy passages that capture ambient light, as well as certain parts of their surroundings, in their shallow but murky depths. These passages are anchored by their juxtaposition with the matte ones that surround them. The shadowy figures that flit across them, as well as the luminous glow they take on, both place them in the world, and remove them from it—they make use of their surroundings as a compositional element while standing steadfastly apart from them. What becomes incorporated in the surface of “Doubleu (Dark)” takes on a different personality depending on such factors as the position of the viewer relative to the canvas, since it is only in relative proximity to it that its dance with its surroundings can be perceived, and the time of day at which it is viewed. Ideally, the painting would be seen when illuminated by late afternoon light, though it can also be lit artificially, and in such cases the glossy bands take on a special prominence as they boldly body forth from the dark ground.

The second is the subtle turning, shaping, and crimping of space Provosty achieves by painting around the edges of the canvas. In “Doubleu (Dark)” a white band curves around the painting’s left and right hand sides while slightly tapered ochre bands line the top and bottom of the canvas, the glossy passages darkening the upper one at the points where they make contact. Hung against a white wall, the edges of the canvas thus dissolve into it without sacrificing the strong, solid, rectilinear impression the painting as a whole also makes on the viewer.

They not only set off the painted field, but also render the space contained within complex. Again, while initially appearing flat, the duration of the viewer’s perambulation of the canvas, and his or her adjustment to its visual cues, permits the viewer to note that the surface, without losing its sense of material presence, has been rendered as if subtly squeezed, crimped, and rotated. The overall effect is not dissimilar to the act of pressing, turning, and otherwise manipulating an object to investigate and contemplate it. All this is kept at the tautest and lowest possible perceptual register so as to ensure that the painting does not devolve into a set of cheap optical tricks.

Paying such attention to these devices is not a formalist exercise (except insofar as formalism, broadly conceived by the likes of Roland Barthes and Roman Jakobson as much as by Clement Greenberg and Michael Fried, provides the necessary methodological basis for any rigorous analysis), but rather sheds light on the nature of the most significant directions being pursued in art today. This relates specifically to the resurgence of abstraction, especially of the painterly variety, which we are currently witnessing, and which is often not largely poorly understood, as it is most often reduced to a redux or update of the canonical abstract painting of the 1960s and 1970s, such as that of Robert Ryman, Blinky Palermo, and Gerhard Richter.

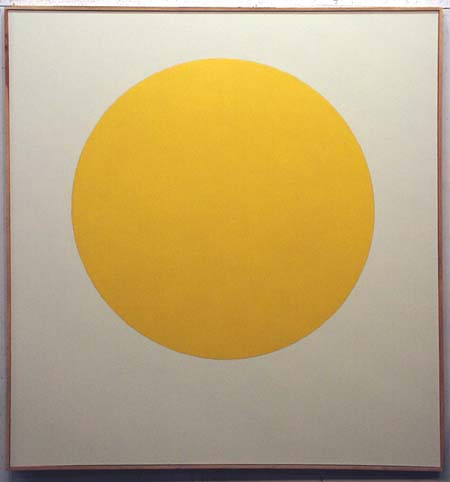

Darby Bannard, Yellow Rose, 1959. Courtesy of the artist.

To my mind comments such as this—which betray a growing skepticism in the 1960s over the status of the object, and the ability for it to ever be fully self-evident to the five senses suggest that it would not be compelling for a painter today to simply take up Bannard’s formal innovation of juxtaposing matte and glossy passages of paint. Rather, if this device is to show up again in art, then it must be put to more contemporary ends. In this way, it is significant that, by working with semi-reflective surfaces, Provosty joins a small, but important group of younger artists.

One of the first, at least of this younger generation, was Jacob Kassay, who in 2005 sent his first acrylic gessoed canvas to a commercial electroplater to be plated with silver. Based in a rigorous conceptual gesture, this removes the artist’s hand almost entirely from the act of creating the work. The resulting canvases are nonetheless accompanied by an equally strong formal result because the plated surface of the finished painting captures light and ghostly reflections of the ambient surroundings that get caught in it, an effect that the artist calls “impressionistic.” (3)

Two of Jacob Kassay’s electroplated paintings

What is important is that the path to get there had to be very different based on when each artist found himself entering into history. Bannard’s skepticism was over the ability of human vision to deliver the “truth” of an object to a particular viewer. In distinction to this, the considered pictorial phenomenology of Kassay and Provosty suggests a farther-reaching skepticism about the ability for any form of perception to ever render such veracity; it is a skepticism about the ability to ever retrieve any kind of ultimate, overriding truth. Bannard’s paintings suggest that perhaps at some earlier point (or if we were just a bit more astute) we would be able to grasp the reality before us. The power of Kassay and Provosty’s paintings lies in the way they make the endless distortions of the digital age meaningful and active, rather than arbitrary and passive, and all this without ever directly referring or alluding to the digital. The gloss and shimmer by which they re-present ourselves to ourselves is evocative not only of the filter on an Instagram image, but also of a certain failure of transcription that those filters reveal in their pretension to allow their users to seamlessly cover over errors in color balance, lighting, etc.

The framing and manipulation of pictorial space by the bands along the edges of Provosty’s paintings also suggest this, as well as the fact that our task is not to surmount these distortions, but rather to learn to be aware of them, and to bend them to newer, better aims. Similarly, it is not unsurprising that Kassay has recently been focused on an even more conceptually oriented series of works where the remainders of canvas left over from the production of the silver paintings are framed, as is, on specially made stretchers that perfectly follow the contours of those scraps. These works conceptually “frame” the silver paintings by presenting for our intellectual and formal contemplation the typically invisible and extra-artistic refuse of painterly production, and in doing so act as a materialist complement and anchor to the aesthetic vision of the silver paintings.

However, neither the skeptical position of the 1960s nor the more open and embracing one of today is better than the other, for both are conditioned by the demands history makes of artists in terms of presenting the issues that beg to be confronted. In the 1960s it was enough to tackle the means by which the senses process the meaning of things in the world, as Bannard’s paintings do. Today, though, to do this is to risk losing ourselves within an infinite regression that removes from us all agency and breeds complacency.

Recognizing the insurmountability of the system is not to succumb to it, but rather to envision a heterotopia of alternate ways of existing within it. The particular heterotopia that Provosty’s paintings (as well as Kassay’s) suggest is one where the seemingly endless flow of information, and all the networks within it can be mobilized so as to not be passive. One of Provosty’s major contributions is to suggest that we both be aware of our placement in the world, but not too hung up on how we circulate in it. “Doubleu (Dark)” simultaneously embraces us by mirroring aspects of ourselves and our surroundings back, rejects us by limiting these reflections to shadows passing over and in a surface, and allows us a certain agency by having the nature of the pictorial space change with our movement and position.

1. Rosalind Krauss, “Darby Bannard’s New Work,” Artforum IV:8 (April 1966): 32.

2. Krauss, “Bannard’s New Work,” 33.

3. Jacob Kassay in “Jacob Kassay with Alex Bacon,” The Brooklyn Rail (forthcoming, December 2013/January 2014).

4. Ad Reinhardt, “Black as Symbol and Concept,” in Barbara Rose, ed. Art-as-Art: The Writings of Ad Reinhardt (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1975), 87.