Islam & the Imagination: Notes from an American Artist in the 21st Century

Zain Alam

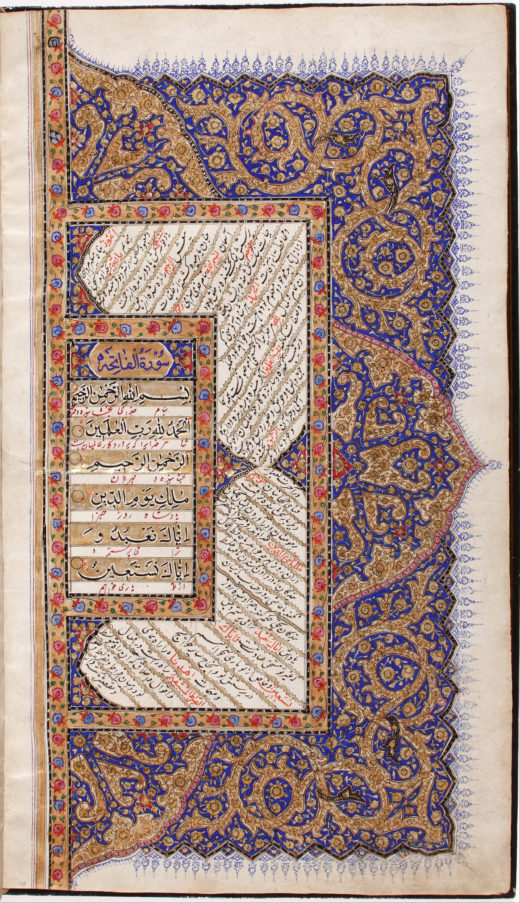

Quran, 1770-1800. Courtesy of the Museo Lázaro Galdiano.

Quran, 1770-1800. Courtesy of the Museo Lázaro Galdiano.

By Time.

Indeed man is in loss,

Except those who have faith and do righteous deeds, and enjoin one another to [follow] the truth, and enjoin one another to patience.

— Quran, “Al-Asr: The Declining Day”

God has never sent a prophet without giving him a beautiful voice. — Hadith of the Prophet

I am a Muslim. Minutes after I was born at the Flushing Hospital in Queens, New York City, my father whispered the shahadah into my ears: La ilaha il-Allah—There is no God but God. I was introduced to Islam with the world, and the rhythm of La ilaha il-Allah took the place of my mother’s heartbeat. All other experiences were subsequent to the rhythms of Islamic verse. In my childhood home of Kennesaw, Georgia and in cities across South Asia, I’ve heard the shahadah repeated daily in the azaan, which calls believers to prayer. No one disputes the beauty of the sound—the strong and sonorous voice of the muezzin casting a spell on its surroundings. At home, recorded azaans are played back by apps that have re-placed miniature mosque-shaped alarm clocks that double as home decorations. But their intention is the same: to invite us to prayer regularly, five times a day.

I am a musician. My songs take on new lives apart from me the moment they are shared. The long process of songwriting is how I try to do justice to what begins as a melody in a dream. My task as a composer is simply to submit to the dream, guiding it to structure and feeling it into form, through a private intuition that is informed by deep traditions. I may not know why singing songs—even when I’m alone—brings me such pleasure, but sharing them with others comes from a desire to make something that can find a life far beyond my own.

Make beautiful your voices while reciting the Quran. — Hadith

![]()

Like most Muslims, I’ve memorized many verses from the Quran in their original Arabic, despite not understanding the language. My mother tongues are English and Urdu, the language my parents grew up speaking in Pakistan. My mother, grandmother, and Islamic Sunday school teachers all took part in teaching me how to recite the Quran as a child without ever simultaneously learning to understand it. Sunday school was at al-Hedaya Mosque, right off the highway in a converted house in nearby Marietta, since we didn’t have one in Kennesaw. I often cried before being dragged to lessons and dreaded going for years, unable to understand the point of it all. But my inability to understand the meanings of the words encouraged me to appreciate the poetic, musical qualities of the sounds and structures of Quranic Arabic, thankful for the rhythms and melodies I internalized through countless hours of recitation. I also gained an aesthetic appreciation for the visual beauty of Arabic calligraphy, as inscribed in mosques, homes, and Qurans all across the world. Islam is a supremely aesthetic religion. Between the acts of recitation and calligraphy emerges an enormous expanse of sonic and visual beauty.

Sharing my songs with friends and loved ones is one of the last steps in the composition process. Private devotional practice becomes a public performance, which extends beyond me to listeners whose receptive faces are sometimes the greatest feedback. At this point little, if anything, will change, but the shared moment of reflection helps settle any lingering concerns before setting the song in stone.

Do they not then reflect on the Quran? Nay, on the hearts there

are locks. — Quran, 47:24

![]()

By middle school, I delved deep into online commentaries and translations of the Quran. 9/11 ensured that my faith could not remain a casual concern. What did it mean to be Muslim when your religion was how you were other-ed by peers, and even by other people of brown skin who distanced themselves from you as a precaution? To be questioned and harassed about my religious background meant I needed to have my theological bearings in order, and a devout practice followed as a result. Part of Islam’s beauty for me has always been the fervor it induces in its believers. I wavered for a time in high school and college after finding certain fatwas and orthodoxy troubling, but the intensity for ideas—of submission to discipline, the Oneness of existence, a struggle to find the Undefinable—never faded.

Back in Sunday school, I had found it unsettling whenever teachers batted down my questions for going too far. They deemed innovation, known as bid’a, to be wicked and harmful to our community. We were to unconditionally trust the Elders before us, and take the word of God as final. Their Islam allowed for no ambiguity, far unlike the Islam I began to find through my own studies.

I stumbled upon the idea of ijtihad as I dove deeper into translations and commentaries of the Quran while in high school. Related to the infamous jihad, ijtihad literally means the act of exertion or endeavoring. Ijtihad in a religious context refers to finding answers and asking new questions of the religion that reflect one’s own time and place.

The finest thinkers in any civilization carve out their own world of habits and actions, each of which is pursued not for its own sake—like Muslims fasting in Ramadan or reflecting on the Quran—but as a means of perfecting their lives as a whole. They leave behind noble legacies and systematic traditions that will become guides for their descendants. Generations connect through the ijtihad of practice, and adapt these guides, reinterpreting inherited forms with fresh personal vision or experience. The souls of one’s ancestors are reawakened through their heirs. Ijtihad in this way resembles the same kind of delight that Islamic philosopher and mystic al-Farabi proclaimed as emerging from the discipline, refinement, and habit of creative, critical practice. He came to a balanced view on the nature vs. nurture debate with a belief that exceptional individuals are not only born with exceptional ability, but also require an exceptional dedication to self-refinement. In other words, a child becomes a prophet ready for divine inspiration only once he or she works the natural, passive intellect into an active intellect through years of acquiring knowledge and perfecting spiritual practice. This transformation is akin to Aristotle’s perfect union of existing matter and potential form; here, ijtihad becomes the personal union of both theoretical and practical faculties that manifest as ideals of the soul’s rational faculty.

So the idea of bid’a is then not a ban on change, but a criterion for fresh interpretations of texts so that they fit Islam’s core principles in response to contemporary life. Scholar Umar Farooq Abd-Allah points to this as a way of balancing creativity with continuity in tradition. Limits do not hamper creativity, but give it a basis and direction from which to bloom.

Every Muslim must practice ijtihad to determine what school or scholar they should follow. Islam is a religion without any central authority—there is no Pope—so ijtihad is vital for communities to reevaluate how inherited standards apply in a new time and place.

Putting together all of the parts to a song is a long process, even after I have found the melody and initial structure.Looped sounds at this stage become my touchstones for establishing rhythm and evoking memory. Sources range from field recordings made during my travels through South Asia to old guitar demos from my personal archives. Loops from these times conjure an immediate comfort through familiarity alongside a foreignness that grows when you repeat anything for long enough. The fertile space in between—for example the interplay of train and bell rhythms, or the ambient sound of a Muslim neighborhood in Lucknow, India—offers a sonic world safe to play in but also wide open for surprises. Knowing these sounds intimately on their own terms but in the context of my life is how they come to function like an instrument, with an instinctive feel so that intuition guides the compositional process before intellect.

Completing the song only feels close once the very last details come into play. And sometimes it may take months of reflection before I feel secure sprinkling just the right mix of ornamentation on top. Layers of noise as accents, found sounds as narrative transitions, and effects like reverb, distortion, delay—these are what make a song coalesce and grant digital recordings the illusion of existing in physical space, possible only by time and my patience.

Recite the Quran in a measured pace. — Quran, 73:4

![]()

After frequenting a mosque for long enough, I become attuned to its particular way of reading prayers. The slightest variation from routine is immediately noticeable. And variation is a praiseworthy practice. Habits are not ends in and of themselves, but serve as roots for a lifetime of learning. Slight changes to solid foundations are how one perfects the art of reciting God’s Word.

In my religious practice, I try to habituate personal reflection about the style of my conduct and the substance of its meaning so that such inquiry becomes instinct, just like prayers or the shahadah. This is how I stay alert, focus on beautifying my expression, and remember why any of this matters in the first place.

I introduce my melody to other sonic materials once it feels secure in substance and structure. I may down-tune my guitar to write a bass line or sing new melodies that become accidental harmonies. Finding the tempo and rhythm of the song-to-be is itself a devotional practice that takes patience and a calm hand.

To force one’s judgment on material too early will stilt the feeling that birthed the song. And playing with the song in different moods and settings is an intuitive way to find its rhythm. Once the song pulses through my life like a ritual of its own, my body pinches and pulls at every tempo shift, even if just a few beats per minute, before settling in to tell me it’s found just the right groove.

Say: Travel through the earth and see how Allah did originate creation. — Quran, 29:20

![]()

Islam insists on strength of belief, discipline, and self-reflection. Islamic philosophers like Averroes assert that this is exactly the point of the vivid stories told to us in the Quran—to put a memorable face on an otherwise complex ethical framework. Consider the tradition of Asma-ul-Husna, the 99 beautiful names of God: The Sublime, the Beautiful, the Patient, amongst many. The list points to God’s Oneness as the first manifestation of the ultimate beyond, unique and above all perceptual powers, as well as all subsequent manifestations of the Divine. For philosopher Ibn Arabi, Adam was superior to the angels because of his ability to begin seeing the diversity of these manifestations through their physical and particular ideal forms in spiritual experience and the physical world.

The Angel Gabriel’s first instruction to the Prophet was to first recite the Quran and then read it for himself and for his community in order to integrate its teachings into their lives. We too must recite the texts of the faith and read it in the context of our lives, rather than let another do it on our behalf. To grow up with Islam and believe that submission to someone else’s reading of the faith without personal struggle and adaptation into one’s own life is mind-boggling. How can one claim to have faith when they have not wrestled with what it means to take a stance not only on lifelong matters like diet or dress but also on those that can never be directly known like the nature of consciousness or an afterlife? To then displace that struggle into violence is the greatest perversion of the Islamic idea to discipline one’s self.

Only once I know what emotion a melody triggers in me can I use the scalpel with great care, deciding which notes are essential, where in time they belong, the dynamics felt in between them. Arriving at this stage without devoting myself to the melody results in something perhaps formally sound but emotionally hollow. One can always hear when a sound that once had spirit has been sanitized for structure. I may still end up with the same stiff result if I do not also listen for fine, unexpected details perhaps more beautiful than the notes they decorate. I can take these gentle, subtractive steps only once I have devoted enough time and energy—conscious and subconscious—to know the sounds intimately.

For a faith that calls itself a way of life, moral means must take precedence over ends that are time or culture-specific. Ethics give life a dependable shape and rhythm, pinched and pulled until they fits our context perfectly. Niqab, the number of times to pray a day, polygamy: none of these are core tenets of the Quran or reasons to go at one another’s throats. Our eyes have to be on the more important values at stake often lost in present debate. The nature of Oneness, the practice of discipline and sacrifice—these are the special ideas worth cherishing. In our distracted and multitasked age there is a reason why daily prayers and a month of fasting inspire awe in others—not simply as physical feats, but as embodiments of patience and struggle.

The stories, songs, and poetry we inherit are the vehicles for our values. We are tasked with their reinvention through the aesthetic sensibility of Islam inculcated from birth and deepened through creative practice. Most Muslims give little consideration to such practice yet extol the long history of Muslim achievement in the arts and sciences. The golden age of Islam is a crucial history for us to share and remember, but why not also emulate its examples? For Averroes, his life’s work in philosophy was a means of following the Quran’s instruction to reflect on our world and appreciate it as the work of the Divine. To do that requires building on the past—including the past of non-Muslims, in the same way Islamic intellectuals preserved and pushed forth Greek philosophy during Europe’s Dark Ages.

There is plenty of beauty and wisdom in our own traditions that no one can take away from us. Our work is to listen to what they said, frame their words for our time, and polish their beauty against the wear and tear of history.

After some time growing comfortable with a melody, I ask: how does it make me feel? I am not classically trained in music and instead count on years of growing up with Bollywood and the Western pop canon, alongside Islamic prayers in all their play with melody and modulation. My subconscious mind knows my own melodies often fall somewhere in between these traditions, each triggering strong emotions from memories which also fall somewhere in between. There’s no need to force them to fit one way or another—in dreams, they are allowed to simply be.

For each (such person) there are (angels) in succession, before and behind him: They guard him by command of Allah. Allah does not change a people’s lot unless they change what is in their hearts… — Quran, 13:11

![]()

Perfection at the level of the Prophet is the aspiration of Islamic practice. If we follow the foundations of a progressive spiritual path and find a way to make it beautiful as well our own, there is no reason for our practice not to trickle into every aspect of our lives. How we care for others, the honesty of our work, the respect we give to elders: with the diligence and devotion our faith demands, it should shine through everywhere.

Fresh after waking in the morning, my first impulse is to grab my phone and record the melody from my dreams before it is lost in the noise of the day. I will hum the melody, strum it on my guitar, pick it out on the piano through the day so its memory becomes habit. Now is not the time to ask too many questions or suggest corrections: like a lover, the melody must feel at home, welcome, showered with attention, growing comfortable in each other’s presence. I keep repeating the melody, caressing every note in whispers, until I know just how it feels.

Invite (all) to the Way of thy Lord with wisdom and beautiful preaching; and argue with them in ways that are best and most gracious: for thy Lord knoweth best, who have strayed from His Path, and who receive guidance. — Quran, 16:125

![]()

A generative rather than reactive outlook is an effective strategy in combatting Muslim stereotypes these days. Beauty invites engagement, and its contagious energy can work wonders in our communities. al-Farabi once wondered if we are all connected by the emanation of Divine love—a love which manifests in us as an attraction to Light as revelation, to the world as guardian, to our ancestors as guides. The Divine is beyond all human comprehension, but perhaps we may point to this simple connective energy: the very fact that things exist and live in natural beauty.

Since began studying Islam in Sunday school. I have asked in some shape or form: what does the primacy of Oneness mean in Islam? A tyranny of thought or something philosophically far grander? I have felt it to be a unity of being, an irreducible principle of existence that joins and defines us against Nothing—the fact that things do not exist. A Oneness that insists on difference as inherent to the realization of inclusion, even in its own 99 beautiful manifestations of mercy, wisdom, sight, and sound, amongst many. A grappling with the limits of our knowledge, and a Beyond which grants potential forms their actualized presence. Art and ritual are vehicles of mystical experience which come closest to finding the Divine in this world.

Islam is my heritage: what I hold dear is the core fact of Oneness and the discipline to find it. To recite that fact and inscribe it all across the world with a touch of beauty is the highest form of prayer.

My songs have always begun as songs that trickle down into my dreams. In the Quran, sleep is compared to death. God takes our souls before returning them once we awaken, whereas in death the final return is to the Divine from which we all begin. There is a long Islamic tradition behind the interpretation of stories—dreams included—sometimes called a science. But for me, these hymn-like visions demand less critical thought and greater contemplation. So instead I watch and listen as notes play to a pulse, whirling in circles until they take form.

In this contemplation I also stand in awe of how many stars aligned to generate this melody. How and from where did it come? It may be luck, nostalgia, some morsel of aural inspiration from the day before, or a combination of them all. The song begins as a grain-sized seed before branching out into the mosaic of a song with innumerable causes and materials to thank for its existence. It exists, but it just as easily could have not.

Watching the evolution of a song in reverse—or of life in general—I observe innumerable ideas branching off stems from other ideas which all fold back into a seed. And then this seed flies through space and time back into the arms of another seed. The cycle continues again and again. Yet there must be some seed, some initial cause to end this infinite regress. Whatever is the cause for the beauty of the world in its diversity must be perfect in its completeness, able to give rise to such multiplicity, entirely free from any other causes like form, matter, or aim. These qualities would make it just like the rest of anything else we observe, as remarkable as the world. Rather, this is the principle that is just necessary of existence: what has no beginning, no end, permanent, independent, belonging to nothing, and thus endowing everything else that exists with all the spatiotemporal properties we otherwise know as the world.

With the help of this spiritual realization and gratitude for the gift of musicianship, I too may endeavor to bring forth what begins as a nebulous dream into an object that occupies space and time. Writing music for years has trained my subconscious to loop the melody into memory before it slips away. My critical faculties cannot disrupt the creative process, since they sleep until it is time to rise. Contemplation and spiritual stirrings are more than enough to guide and protect the melody before it reaches the light of day. Where the sounds all come from is beyond my knowledge; all I can do is pursue them.

Per Islamic custom as I first witnessed when my uncle passed away, someone will whisper into my ears the shahadah when I die: La ilaha il-Allah—there is no God but God. From where all existence begins, all existence must return.

Zain Alam is an artist whose work explores South Asian artistic traditions, transnational movements in the Islamic world, and diasporic identity in the U.S. He is presently a BHQFU Fellow at ArtCenter/South Florida, a graduate student in Islamic studies at Harvard University, and the frontman of the NYC-based recording project Humeysha.