Gold and Ice Cream: Two Paths for Colombian Contemporary Art

Hunter Braithwaite

Ernesto Neto, Lanavemadremonte (Mothership), 2013. Polyamide fabric, pantyhose, cardboard, sand, nails, plastic balls, rubber, styrofoam and aluminum tubes.

When you visit Bogotá, they tell you to go to the Gold Museum. They tell you to go to the Botero Museum, which is around the corner and shares a courtyard with the Museo del Banco de la República. They tell you to take the funicular up to the church on Monserrate, but you mustn’t move too quickly, because the city itself is 8,661 feet above sea level; in the mountains it’s over 10,000. Yes, many suffer from altitude sickness, which shares its symptoms with the flu, carbon monoxide poisoning, or hangover. While you’re here, you need to drink aguardiente, you need to eat chicharrón, have you visited the Gold Museum? Oh, and don’t get into a cab, or you’ll be kidnapped.

I heeded the last one, walking three miles across industrial Bogotá in the dark, happening across a working class bar called ROCKOLA BAR: DONDE YEYO (even with my nonexistent Spanish, Debbie Harry popped into mind). I had been trying to find the Corferia, where the 9th Edition of artBO was being held. This was as good a place as any to have a beer. After several of which, (it wasn’t a Debbie Harry kind of place after all) I made it to the fair. There were 65 galleries from 23 different countries, mainly from Latin America. Additionally, there was the Laboratorium, a selection of 14 individual projects having to do with science and art, a lecture series, and the Articularte Pavilion, a platform for arts education put together by Nicolás París, along with Maria Camila Sanjinés and Manel Quintana. Unlike the gargantuan sprawl of Art Basel, it was blissfully easy to traverse. In fact, even the work itself was easy to traverse. While on the up and up, Bogotá’s art market still has a ways to go. Galleries, wooed to Colombia by local collectors, still bristled at the thought of shipping and paying customs on large sculptures when they were just going to go unsold. It was an entry-level fair, with the upper end of the price point about $25,000. There’s no shame in this game. Art fairs beget manageable art, and artBO was no exception. In scale, price, and form, most of the pieces were apartment-sized.

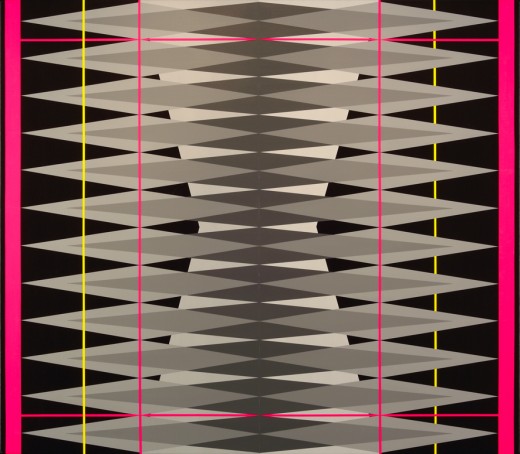

But perhaps the nicest thing about the fair was not knowing any names. There is seldom any difference in the fairs except for the graphic design on the tote bags, and it does get quite depressing to accept that the convention center is sometimes no more than so many binders of acetate-sheathed trading cards, with the artists themselves—“I’ll trade my Ken Griffey, Jr. for your Ken Price”—privy to similar diminution. It was refreshing approach the work afresh, to stumble over names, to have to actually describe the pieces after the fact. I saw grids of mostly black and white photographs. I saw literal documents of Colombia’s recent history. I saw minimalist abstractions executed with a distinctly Latin American sensibility—this seems a strange thing to say, but the reduced cruxiforms of Manolo Vellojín and the neon indigenous patterns of Pablo Griss speak for themselves. That the former artist recently died, and the latter is a young man showing in a booth with Peter Halley, perplexed any summarizing but was nevertheless invigorating to my eye.

Pablo Griss, Intervention: Black Magenta Yellow, 2013, acrylic on linen, 41 x 48”. Courtesy Klaus Steinmetz Contemporary Art.

But as is usually the case with these types of trips, things didn’t really click into focus until the free afternoon. In the Candelaria neighborhood, there is the Museo Botero and the Museo del Banco de la República. Not far from that is the Gold Museum. At the Museo Botero, the iconic Colombian’s paintings of fat people being fat are hung alongside painters like Bonnard, De Chirico, and Alex Katz with baffling and courtly dignity. The transfusion of wealth and taste is complete, and all the viewer has to do is wait until it doesn’t feel strange. To make this point resonate locally, the Miami reader should lean back, close their eyes, and draw up plans for the new Herzog & de Meuron-designed Britto Art Museum Miami.

But to truly appreciate artBO, you must go to the Gold Museum. For all its successes, the fair had nothing on the centuries of polished fetishism on display in those dimmed halls. Colombia has experience with a certain type of commodity: gold, then cocaine, and now contemporary art. Not that they are unrelated. I had heard a rumor once that in the 1980s, narcos would launder money through Boteros. One would buy a Botero in Bogotá, move it to Mexico City, and then sell it. I asked a curator about this, and she laughed at me. “That’s ridiculous; it wasn’t just Botero.” Another one told me that wealth had become a stigma in this part of the country. Affluence meant criminality. To counteract this, both affluent and criminal read deeply, invested in the arts, and made themselves patrons. In these conditions, the graft of contemporary art was taking, quite easily. ArtBO has led to other art fairs such as the Odeon Contemporary Art Fair and Feria del Millón. But the question remains, do we need any more fairs?

II. MEDELLÍN: ICE CREAM

Victor Gaviria’s film Rodrigo D: No Futuro follows a teenager along the fringes of the Medellín punk and metal scenes. He’s looking to escape the poverty and violence that surrounds him, but if the ethos of “no future” meant anything in ‘70s London, it really meant something in Pablo Escobar’s Medellín. The film premiered at Cannes in 1990. Before it was released, six of the teenage actors were killed in the violence they portrayed in the film. In Medellín, violence was a given, and art, as the director says in the film’s memorial postscript, “ensures that at least [our] images might live the lifespan of a normal person.”

The city has completely changed in the intervening decades, but art’s mission hasn’t diminished. I flew in for the 43rd edition of Colombia’s Salón Nacional de Artistas. The Salón, which began in Bogotá in 1940, has slowly evolved in size and scope. This year, it had the tinglings of an international biennial, not least because the curatorial team opted to place (inter-) before nacional. Under the direction of Mariangela Méndez and a team of curators—Florencia Malbran of Argentina, Javier Mejía and Óscar Roldán-Alzate of Colombia, and Rodrigo Muora of Brazil—the Salón took place in four venues across town, and included the work of 100 artists from 24 countries.

With the Salón’s knowledge game of a theme—Saber Desconocer (To Know Not to Know)—one could be forgiven for expecting an encore of Massimiliano Gioni’s Venice or Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s Documenta, which both sought to dismantle our ideas about our ideas. Yes, the Salón similarly contrasted the contemporary art world with the rich indigenous culture of Colombia and the surrounding region, creating a cross-section of faith, heritage, skepticism, and criticality. However, mapping the terrain of human knowledge and understanding was a secondary mission, behind occupying the physical terrain of Medellin.

Venues included the Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín, the Museo de Antioquia, the Edificio Antioquia, and the

Jardín Botánico. The Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín is housed in a metal factory, a long hangar of a space with two wings that were curatorially opposed (one represented knowing, the other: not knowing) and joined together by a large sculpture by Ernesto Neto. That sculpture, “Lanavemadremonte (Mothership)” (2013) enlarged the arachno-eroticism of a Louise Bourgeois to the size of a bounce house. Upon removing their shoes (and metal jewelry) visitors were allowed to crawl into the sculpture, resting in an uncanny hive of bean bag chairs. I can easily imagine this being a crowd favorite. And there were crowds. As of October 10th, 435, 678 people visited the exhibition venues of the Salón.

Alejandro Mancera’s La Heladería (The Ice Cream Parlor).

This was most clear in the La Heladería (The Ice Cream Parlor), a bar and coffee shop designed by Colombian artist Alejandro Mancera. The Ice Cream Parlor filled the first floor of the Edificio Antioquia, a dilapidated office building re- habilitated for the Salón. On a Monday evening I sat there, drinking a beer and going over my notes. Upstairs there was a lecture and a launch party for a book about Colombian artist Juan Fernando Herrán, yet as people walked through the doors, only about half made it to the second floor. This wasn’t the old game of sticking close to the bar until a boring lecture wraps up; half of the crowd was just coming for an after-work drink and a conversation. As was the point. The Ice Cream Parlor eschewed the VIP lounge of the art fair, and thus the VIP. It also avoided the pedagogical model (the lecture series, the archive) often deployed by curators with the naïve belief that the average person will care. Simply put, it provided a safe, lively place to meet, where culture was available but unobtrusive. In this, it is analogous with the Salón itself, and with the growing art scene in Medellín. No future no more.