Cobra: Bonnie Clearwater and Alison M. Gingeras

MIAMI RAIL: Alison, the first section of your catalogue essay is titled a “(re)introduction” to Cobra. You quote Griselda Pollock saying that it’s not enough to resuscitate forgotten histories, but that we also need “to point the finger at what rendered these things invisible in the first place.” Could you expand?

ALISON M. GINGERAS: The prefix of “re-” is essential because Cobra is not completely unknown outside of United States, nor is it unconsidered in a more rarified academic or scholarly context. “Re-” is also crucial because I’ve been approaching this exhibition with a kind of urgency that is fueled by the group’s contemporary resonances, not just because of Cobra’s historical importance as such. My curatorial and writing practice for this show has not been from a “pure” museographic or encyclopedic approach—it takes liberties and makes arguments. As a result, certain artists who were part of Cobra are not part of this exhibition; it’s not an exhaustive overview of the movement. The argument foregrounds certain figures to counteract the amnesia of either present-day artistic practices, or to foreground Cobra’s politics and sensibilities that are meaningful in terms of our contemporary moment.

In regards to the Griselda Pollock quote, Cobra’s relative invisibility (or more precisely, their deliberate exclusion) in an American context could be explained in a three-fold manner. The group’s unabashed embrace of Marxism from the late ’40s onward made them “difficult” for American institutions in the Cold War period. This is best embodied by Asger Jorn’s continued political writings, his refusal of the Guggenheim Prize, and so on. Secondly, the artists’ insisted on the inseparability of their political, social, and aesthetic practices—hence making them difficult to “market” in a commercial context. And finally, numerous Cobra artists (at least in their official period) actively thwarted the celebration of individual artistic genius. The group— especially Jorn and Constant—worked tirelessly to deflate the mythology of the artist as a singular force or the maker of individual expression. In their eyes, art had a responsibility to explore collective social agency and commonalities that could bring on revolutionary change in society. The last thing they were concerned with was selling their paintings or securing solo museum shows to advance their individual careers.

BONNIE CLEARWATER: The point of entry for Cobra in America influenced our reception of the movement. For instance, when Frank Stella came to see our exhibition The Spirit of Cobra last year, I was surprised when he told me that he was introduced to Cobra while he was still in high school, at Phillips Academy. This would’ve been at exactly the same time Cobra was happening, in the early 1950s. He said that at the time he primarily knew Karel Appel’s painting and that he particularly liked the big globs of color, which was different from the minimal direction Stella followed, at least until his work of the 1990s.

Stella also remarked that Hans Hofmann was very big at his school at the time and Cobra was seen as a wilder version of Hofmann’s use of color, push-pull, and tactile approach. So Appel and all of Cobra were introduced in the United States from a formal point of view, rather than from a political, social, or theoretical point of view. Cobra’s other point of entry was when Appel was included in MoMA’s New Images of Man exhibition in 1959, organized by Peter Selz. The exhibition’s emphasis was on the persistence of the image and the figure in modern art at a time when abstract painting dominated the New York school.

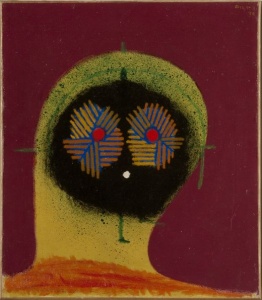

Asger Jorn, Head, 1940. Oil on canvas. NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale; the Golda and Meyer Marks Cobra Collection, M-226 © 2015 Donation Jorn, Silkeborg/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/billedkunst.dk

CLEARWATER: Stella also noted in our conversation that he considered the difference between the New York school and European artists to be that in Europe they could never give up the figure, whereas in the United States it was all about abstraction. I realized that this initial reception was why Cobra has been misunderstood in America and why we need to reinvestigate it.

GINGERAS: There are also new voices coming into the reconsideration of Cobra—a new generation of scholars from the United States, Belgium, and Denmark who’ve begun to translate important primary texts by Jorn and others as well as challenge the stilted narrative of Cobra as a Northern European style of painting. Through this new scholarship and writing, a fuller picture is beginning to emerge in terms of what Cobra was about, and has even begun to assert a new pantheon of the key protagonists. Until recently, it was almost impossible for a non-Danish or non-German speaker to read the theoretical or philosophical writings of Jorn and others of his circle. Recent publications, such as NSU’s War Horses: Helhesten and The Danish Avant-Garde during World War II, or Karen Kurczynski’s The Art and Politics of Asger Jorn, have thrown new light on the prolific, polymathic practice of Jorn—who is, for me, one of the eyes of the storm of this movement.

This gets back to one of the most important arguments I hope to make with our show, that Cobra is not just a three-year period that should be imprisoned in a reified ghetto of northern European art. Instead, it’s probably one of the longest-spanning international avant-gardes—if you buy the argument that it begins with the Helhesten group in 1940 and ends with the deaths of Jorn in 1973 or Christian Dotremont in 1979. Embracing this multitentacled, multinational movement across these decades through the central nexus of aesthetic experiments, socio-political values, and internationalism is the key to opening up the traditional definition of Cobra and expanding previously narrow understandings of the group.

CLEARWATER: Kerry Greaves, who curated the exhibition War Horses for our museum, pinpointed what I consider the fork in the road for post–World War II American and European art: at almost the same time Jorn promoted the idea that kitsch and everyday life were essential to art, Clement Greenberg wrote that there’s no place for everyday life and kitsch in art. Consequently, in America, artworks are seen as autonomous objects, rather than as part of the social experience of the art, whereas the attitude of the Cobra artists and subsequent experimental European artists eroded the boundaries between life and art right from the beginning.

RAIL: Bonnie, how did the museum come to have the largest collection of Cobra in the country?

CLEARWATER: The Miami collectors Dr. Meyer and Golda Marks were consumed by Cobra, which they began collecting in 1958. They amassed one of the largest private collections of the movement and generously made their first donation to the museum in 1978 and subsequently made an additional gift in 1989, bringing their total gift to more than 3,000 works. This gift formed one of the museum’s core collections. Two years ago, the museum embarked on a series of three exhibitions based on our Cobra collection, funded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, that has generated considerable new scholarship and built a wider awareness of this movement.

RAIL: Why is it important to look back at the movement right now?

GINGERAS: One way to answer this question is to propose Cobra’s legacy as an alternative genealogy for a range of practices that do not emerge from American postwar hegemony. There are numerous contemporary artists, such as Mark Flood or Bjarne Melgaard, who are frequently allied with “post-Pop” because they deal with “low culture,” but I would argue that in fact these practices emerge instead from Jorn’s politicized—dare I say—revolutionary ideas about art being a fundamental expression of human community.

When he wrote his essay “Intimate Banalities” for the Helhesten journal in the 1940s, Jorn celebrated the “anonymous artists, folk art, the Sunday painter” and he sought to glorify these expressions (non-ironically) as equally valuable as the great classical masterpieces of culture. When Mark Flood—an artist who, in my mind, is directly descended from the DNA of post-Cobra Situationists via the Houston punk scene—recuperates a tacky thrift-store painting and paints over it, he is not rehearsing American Pop or appropriation art. He is building on Jorn’s ideas of anti-classicism, of collective authorship, and celebrating the continuity of human culture from the bottom up. The parallels between Flood’s own writing and those of Jorn are uncanny—Flood’s idea of “Culturecide” to me is an American update on “Intimate Banalities.”

CLEARWATER: It also explains why the perception of Francis Picabia’s late kitsch paintings has changed as well. Although he was one of the first abstract painters in the early twentieth century, by the mid-1930s he appropriates kitsch and banal imagery in his painting. I think this gesture was to some extent his response to the Nazi regime’s “degenerate art” exhibition held in 1937 in Munich. After all, his very early abstract paintings and Dada work was denounced in this exhibition. At the same time, the Nazis were extolling what we consider a kind of kitschy figurative art. In this body of work, Picabia seemed to be questioning why his abstract and Dada work was considered degenerate while the Nazis hailed sentimental, figurative painting.

GINGERAS: Picabia was deliberately being antagonistic on both sides of the political spectrum!

CLEARWATER: Which, in a way, is how the Helhesten group—Danish artists who organized under German occupation— was able to create art that subverted the occupiers. Their situation was unlike that in most of Europe during World War II. Many of the artists in Germany and Paris during the late 1930s and early 1940s were forced to flee or perished, so there was a rupture in the continuity of modernism there, but the artists in Denmark were able to continue working because the Germans gave the whole country a certain amount of latitude under the first three years of occupation. Yet the Helhesten artists continued working in the modern modes of abstraction, Surrealism, and Expressionism as a form of protest and resistance. They not only continued to make these works, they actually organized public exhibitions, and wrote and distributed the Helhesten journal. Their first big show was presented in a circus tent, right next to the amusement park! So it looked from the outside as if it was just another form of amusement and not about art.

GINGERAS: I love the anecdote about how at the end of the war, Jorn and his Helhesten colleagues sent a portfolio to MoMA, with a long letter vindicating what they had been doing—and reaching out for international exchange between avant-gardes at the end of the war (something that seems banal today, but when you contextualize this gesture in terms of the animosity and devastation at the war’s end, was completely radical). MoMA actually never acknowledged their letter or gift, and they never gave these works accession numbers, even though they received numerous original works of art from these artists. The story alone illustrates how it has taken this many decades for the complexity of Helhesten-Cobra’s internationalist project to be clear to us.

RAIL: Can we talk more about how Cobra influenced the present moment?

CLEARWATER: Artists like Julian Schnabel and David Salle were in Europe for their formative artistic years in the early ’70s and therefore had first-hand knowledge of the European avant-garde and they were friends with younger artists like German artist Albert Oehlen.

I learned to appreciate Cobra when I worked with Oehlen on a major solo exhibition in 2005. Oehlen makes it clear that his work comes out of Cobra through Jorn and the Situationists. And when I worked with Rita Ackermann on her solo exhibition in 2012, she also emphasized how her work came out of Cobra. These experiences opened up the narrative of modern art for me.

In the United States, the emphasis was on the individual artist with a signature image—Jackson Pollock’s drips, Barnett Newman’s zip, Frank Stella’s black stripe paintings, and so on. The Cobra artists emphasized working as a collective, which continued to be reflected in the practice of subsequent generations of European artists: Oehlen, Martin Kippenberger, Jonathan Meese, and Ackermann, among others. Working collaboratively also subverts the commercial gallery system, as dealers find it difficult to market.

GINGERAS: In terms of Cobra’s contemporary legacy, it is impossible to make equivalencies because of the totalizing nature of today’s art market and the culture industry as a whole. Take for example again Bjarne Melgaard. He has commercial gallery representation and, to a certain extent, a recognizable style in terms of his paintings, but he very actively tries to subvert his own market by taking on very extreme subjects and by working collaboratively.

I’ve invited Bjarne to exhibit a series of works he made in collaboration with a group of schizophrenic patients. Titled Bellevue Survivors, Bjarne invited these artists to make their paintings on top of his own works. Then he created a whole environment around the resulting works. To further connect to his direct descent from Cobra, Bjarne has augmented this project by remaking Karel Appel’s magnum opus, Psychopathological Notebook. Bjarne has made a radically subversive gesture deliberately wrought with problems for his art dealers. But that’s what makes his work so great, and so relevant to the legacy of certain Cobra ideas.

CLEARWATER: The different ways modern art developed in Europe and the way it is generally understood to have developed in the United States reflects the underlying contrasting attitude Europeans and Americans held toward the concept of progress—the philosophical point of view of positivism. In America, especially through Clement Greenberg’s criticism, there’s the perception that art needs to progress and each progression is good, as it’s bringing it to an ultimate pure art. This progression consisted of the elimination of anything extraneous to pure painting or pure sculpture. By the 1970s, however, it is difficult to distinguish any difference between European and American art as artists on both sides of the Atlantic were creating conceptual or performative work. But there is a difference. In America, conceptual art was perceived as an inevitable step in this process of progress, whereas conceptual and performance-based work was already inherent in the work of Cobra artists right from the beginning. We can see how Martin Kippenberger’s statement “make your own life your work” connects with the roots of Cobra. For Kippenberger and contemporary artists grouped under the relational-aesthetics rubric that has defined much contemporary art since the early 1990s, the situation under which the work is experienced is the artwork; the object is just the remnant of that experience.

GINGERAS: The core of the Cobra group—and in terms of its contemporary resonance and legacy—is their insistence on experimentation. This experimentation was manifold and wasn’t limited to painting and sculpture, nor to the social and political. There is a whole wing, if you will, of Cobra that was grounded in the literary—this is an aspect that we’ve not covered in our conversation and is frequently glossed over, even within the specialist writing on Cobra. Especially on the Belgian contributions to Cobra, the act of writing, the practice of poetry, and the attempt to create the written word into a painterly form (the idea of peinture-mot) was at the center of their experimentation. Christian Dotremont— who was the glue that kept the various branches of Cobra together in the earliest years—was essentially a writer and literary figure. He edited their journals, he wrote incessantly on the artists and on their theoretical and political projects, he performed their manifestos at their first show in Amsterdam in 1949—just this one literary tentacle of the movement is overlooked in the bigger picture of Cobra.

CLEARWATER: What I find fascinating is this idea of inevitability in art that was pervasive in the US art world. By the ’70s there was the sense that conceptual art was the most obvious next step, and almost the endgame to modernism. That is why the 1980s generation of artists got such a tough rap, they were seen as being regressive, as if they were negating that whole concept of progress. Whereas Europe didn’t have this same attitude about progress. As French cultural theorist Paul Virilio has observed, Europe’s anti-positivist attitude was influenced by the way wars caused a rupture with the past. America did not experience this sense of rupture.

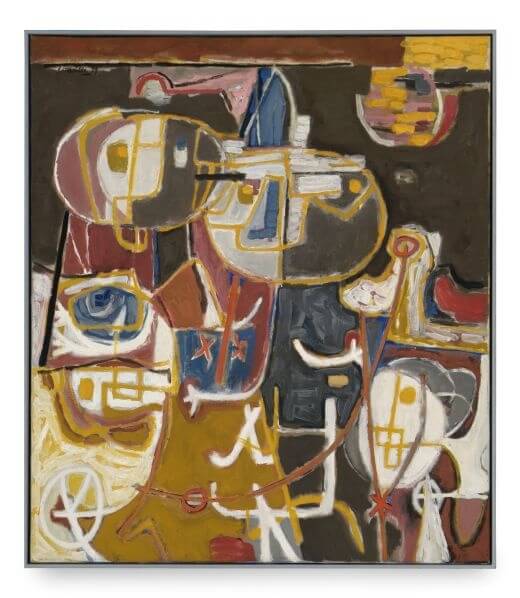

GINGERAS: Even if when you look at someone like Jorn, whose painting practice in the ’60s gravitates more toward abstraction, there’s a refusal to abide by those very narrow, categorical ideas. Instead, Jorn was always about spontaneity, even after the formal dissolution of Cobra. So some of his pictures from the ’60s or early ’70s might resonate with gestural, American abstraction, but there are always little monsters, and faces that come through the abstract passages of the canvas. I think of that aspect of Jorn as a type of resistance to aesthetic hegemonies. There was always an awareness in Jorn—there were so many narratives of art. He used to say that he was part of a continuum of “ten thousand years of Nordic Pop art” when he founded the Scandinavian Institute for Comparative Vandalism. It’s only recently that we (in America) are learning to listen to these other parallel narratives and understand that they were equally—if not more—sophisticated or conceptually challenging.

CLEARWATER: It’s understandable why MoMA director Alfred Barr ignored the exhibition proposal he received from Cobra. He probably couldn’t distinguish Cobra art from what was happening before the war and he was looking for the next new art movement. But to go back to this idea of reintroduction, we have recently experienced a period in art historical research that has greatly raised awareness of the multiple narratives of modern art history and there are new art historians focusing on Cobra. This research has encouraged a new look at Cobra that appreciates it on its own terms, not as a parallel Abstract Expressionism, nor from the perspective of being about the figure versus abstraction.

RAIL: What’s your hope for the general public coming to see these exhibitions?

GINGERAS: I hope that the audience comes to learn about a group of artists that they probably don’t know. Maybe the visual or formal appreciation must come first. A few friends who have seen images of the show were quite surprised by how retinal and engaging the work is. When you say “Cobra,” cobwebs come up in some people’s minds, especially an older generation who was around in the ’60s and ’70s during the first wave of its reception. Datedness or misunderstanding has stuck to Cobra in the United States, because there have only been glimpses of it, like a late Appel painting. Or in some cases, a viewer may have gone to some regional museum in the Benelux countries and seen one Cobra-related show. I’m hoping that with these Cobra exhibitions a seduction happens, first on the level of the eye, and then gradually people become engaged in the deeper level of politics and discourse that was so central to the group—and seems essential to our present day. Cobra historically subverted market speculation, and maybe that is another reason why it’s engaging to think about this group now— since so much of the art we see today has been entirely hijacked by the market or is in direct service of market speculation. They were making murals for kindergartens. They were doing public, collaborative works.

CLEARWATER: I hope these shows help visitors to understand that Cobra works embody these artists’ optimism. The Cobra artists came through World War II believing that, through their work, they could actually make a better world, and could make people feel better, and happier.