A SPECULATIVE STORM: Contemporary Art and Real Estate Development

EVAN MOFFITT

"...flashy, placeless architecture that attracts cultural and economic capital (the so-called Bilbao effect)." The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, designed by Frank Gehry, in Bilbao, Spain.

In her influential 2014 book Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space, Keller Easterling examines the reproducible nature of global infrastructure—from housing stock to telecommunications—as an effect of “multiple, overlapping, or nested forms of sovereignty” that harness the power of the globalized economy.1 In aesthetic terms, this means that a “familiar confetti of brightly colored boxes nestling in black asphalt and bright green grass” visually links the capitols (and capital hubs) of resource-rich, developing nations like China or the United Arab Emirates to “first world” tax haven resort metropolises like Miami.2 Such aesthetic uniformity is incentivized by tax schemes collectively categorized under the UN-administered label “free zone,” which promises foreign corporations cheap labor and utilities, as well as environmental and labor regulation exemptions, in the hopes that foreign investment will jump-start the host country’s economy. But as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development charged in 2010, free zones are “sub-optimal” economic catalysts, more often exploiting day laborers while fattening the wallets of the already über-rich. “The world has become addicted to incentivized urbanism,” writes Easterling, “and it is the site of headquartering and sheltering for most global power players. So contagious is this spatial technology that every country in the world wants its own free zone skyline.”3

Abu Dhabi, with its six free zones, has taken notes from Western cities like Miami and Berlin. Miami has informed its vast new swaths of gleaming white luxury high-rises, and its sprawling suburban tracts of faux-Mediterranean villas on palm-lined avenues. Berlin has informed its dense concentration of cultural destinations. Abu Dhabi is currently constructing its own Museumsinsel on Saadiyat Island, with outposts of Western museums like the Louvre and the Guggenheim built by Western architects (Norman Foster, Frank Gehry, and Jean Nouvel) famous for flashy, placeless architecture that attracts cultural and economic capital (the so-called Bilbao effect). The UAE government is betting that its speculative investment in lavish real estate developments will pay off when international tourists flock to its newest art institutions—products of a simultaneous speculative investment in high culture.

With its own Pérez Art Museum Miami, designed by starchitects Herzog & de Meuron—across from Zaha Hadid’s voluptuous residential high-rise 1000 Museum Tower—Miami is no stranger to the unholy marriage of real estate and art world speculation. The city’s newest cultural institution, the Latin American Art Museum, is the latest example of this union. An animated rendering in a promotional video released by the site’s developer—which could have been edited by the same production team that produces marketing videos for global free zones—shows two residential high-rises towering above a smooth Hadid-esque, deconstructivist building, its cantilevered floors like a series of stacked lily petals. (The museum was designed by Fernando Romero Enterprise, the same team of architects behind Museo Soumaya, Carlos Slim’s lambasted Mexico City treasure chest.) Occupying prime real estate on Biscayne Boulevard, next to Hadid’s high-rise and the iconic Schultze & Weaver–designed Freedom Tower, the project aims to bring expensive art and expensive housing to an area replete with both. Though little has been announced about the towers, it’s clear that the project’s developer, Gary Nader, is imitating the Museum of Modern Art, whose cash cow Museum Tower apartments in Manhattan rake in exorbitant rents for their proximity to the greatest modern art collection in the world.

Of course, certain philanthropic enterprises should be unburdened by journalistic cynicism, such as free, public museums that deliver great art to diverse local audiences. (Billionaire real estate developer Eli Broad was not free of criticism when he built his private museum on land purchased from the City of Los Angeles for a symbolic single dollar.) But the buck does not always stop there. No simple commodity, art is often instrumentalized for profit due to the cultural capital it accrues by association. As Martha Rosler notes in her e-flux journal Culture Class, cities’ decision to label depressed areas “arts districts” is often an attempt to accelerate gentrification by harnessing the bohemian appeal of the artists who work and live there in large, affordable spaces. In Los Angeles, just half-dozen years after a dangerous and depressed industrial neighborhood east of down-town was named the city’s “arts district,” the area is now home to overpriced cafes and juice bars, luxury condos, and the largest gallery complex in the world, Hauser Wirth & Schimmel, which is complete with a farm-to-table restaurant and dog park. Artists have fled east of the L.A. River, south of the freeway, or to other parts of the city. The downtown Los Angeles Arts District was dead on arrival—but then the city government was never interested in preserving a viable creative life for local artists.

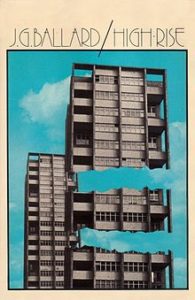

The housing crisis of 2008 began at the margins: banks sold off subprime mortgage loans to aspirant homeowners looking to settle in the suburbs. Now, real estate speculation appears greater at the center, as luxury apartments proliferate in the inner city and skylines fill in with homogenous glass and steel towers. (Most notably, in Manhattan, Rafael Viñoly’s supertall 432 Park Avenue recalls the tower of J. G. Ballard’s 1975 novel High-Rise, a luxury Babel from which the rich survey the poor with an air of excessive hubris.) The structural and aesthetic DNA of these spaces has proliferated in tax havens like a viral code. Culturally and geographically disparate cities like Miami and Dubai have begun to look the same, filled with gleaming residential skyscrapers whose undulating steel facades rise haphazardly next to vacant, unkempt plots of land. Even New York’s historically dense waterfronts have been transformed by ambitious rezoning schemes under the last two mayors, Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg; Williamsburg is now blandly unrecognizable from across the East River, and new luxury condos in Long Island City feed off the presence of MoMA PS1. Despite the shortage of “available,” market-listed real estate in New York, many of these properties remain empty. The “window test” in Manhattan will tell you that, based on always-dark apartments in the city’s residential skyscrapers, one in twenty-five are occupied for less than two months of the year; according to the New York Times, more than half the apartments between East 53rd and East 59th Streets are perpetually vacant, their owners live in Riyadh, Caracas, or Saint Petersburg.4

Cover for J. G. Ballard’s 1975 novel High-Rise.

Perhaps the common property of luxury condos and trendy artworks is that both have become objects of speculation, new chips on the felt tabletop of international finance. (The gam-bling metaphor would be less transparent if the art world didn’t already mirror banking’s use of it.) Many of the industrialists who profit from global “extrastatecraft” also collect art, and so it is only natural that they stockpile their collections in tax-free, offshore storage facilities and residences in cities whose booming real estate markets promise net profits for property sales. Craftier collectors have taken to buying contemporary art, which, if acquired with sufficient market knowledge, can offer staggering returns on investment at relatively low cost to the buyer. Blue chip art, like blue chip stocks, remains stable in value—making it a safe and reliable bet for museums eager to establish their own institutional legitimacy—while a painting by a young New York hotshot can turn over 3,000 percent at auction just a few months after being purchased, as Lucien Smith’s Hobbes, The Rain Man, and My Friend Barney/Under the Sycamore Tree (2011) did at Sotheby’s in 2013.

Is it possible to determine aesthetic criteria that apply to both real estate properties and contemporary artworks that circulate in this speculative market? Clean lines, shiny white finishes, and sculptural surfaces that privilege a stunned, totalizing form of vision—even these resonances would only be conjectural. But it is undeniable that abstract painting and sculpture have long been favored for office and hotel lobby decor, their safe and sanguine subjects free of Marxist critiques or religious and political commentary that might offend the capitalists passing by. Inoffensive architecture craves an inoffensive art. (Dee Wedemeyer might have levied the harshest criticism of Frank Stella, a master in his own right, when she called his colorful Protractor series “the developer’s choice” in a 1985 New York Times editorial, because their scale and color livened up blocky granite reception desks.5) The recent abstract painting phenom-enon known as “zombie formalism” was fueled by speculative auction sales of such blandly salable works, which spent short terms in high-security airport storage facilities in Switzerland or Singapore before swiftly changing ownership. Smith’s own paintings, made with a fire extinguisher, appeal simultaneously to a desire for inoffensive luxury interior backdrops and the bad-boy mythology of the downtown avant-garde, with its notion of original style (perhaps not unlike developers’ pitches for “artsy loft living” to young urban “creatives” who make their livings in finance and tech). Though it’s not always clear who owns such paintings, it is clear that they are more at home behind a Philippe Starck dining table than on the whitewashed walls of a museum.

Globalization now informs the art market just as much as it does finance and real estate. Architectural homogeneity in new urban enclaves is now mirrored by crippling consistencies in new art. Art fairs and auctions too often showcase an appalling lack of aesthetic diversity. As the international levers of money and power come to understand the economic potential of high culture, art’s complicity in rapacious development schemes will grow ever greater. The future of our cities and the integrity of our culture are at stake in this brewing storm of speculation.

1 Keller Easterling, Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space (New York: Verso Books, 2014), 15.

2 Ibid., 12.

3 Ibid., 16.

4 Sam Roberts, “Homes Dark and Lifeless, Kept by Out-of-Towners,” New York Times, July 6, 2011.

5 Dee Wedemeyer, “Lobbies with Stellas: The Developer’s Choice,” New York Times, May 12, 1985.

Evan Moffitt is a New York–based writer and critic, and the assistant editor of Frieze.