Flat Rock at the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami, is Virginia Overton’s first solo exhibition in an American museum. The new freestanding sculptures that Overton created for the show are tenuous yet forceful assemblages of materials the artist encountered around Miami and on site at the museum. The exhibition begins with a large-scale fountain that Overton created for the museum’s pond. In the gallery, she addressed the existing architecture by arranging long planks of lumber to create two parallel lean-to walls; this rudimentary architectural device carves out a long passageway that viewers must navigate before entering a diagonally warped exhibition space.

The exhibition is strewn about the Museum of Art Fort Lauderdale. “Scattered… as stepping stones for the viewer’s passage through time and space” says the museum’s materials. The videos’ peppered arrangement falls quickly into place, acting as nodes of cultural critique, autonomously growing in the rubbed joints of the museum’s authority. Fabri’s “Me and Them” (2005) is one of the first pieces you encounter upon entering the museum’s expansive lobby.

It all begins with a proposal that no one, barring roughnecks lacking any degree of sensitivity, would disagree with: the world is moving too fast. This is also unfortunately becoming a bit of an alibi to not have to think too hard. As the distribution of information accelerates and the hierarchies that once determined the value of its units vanish, experience is impoverished.

The Insomnia Crisis that permeates Karen Russell’s Sleep Donation is already pumping vigorously through the story in the opening pages, but it quickly begins to spread. Insomnia is akin to a zombie plague, but for those readers who are too familiar with endless hours of restless sleep or have experienced jet lag that sucks melatonin to abysmally low levels will find similarities to the horror in Russell’s new traipse

Approximately one fifth of all elephants in North America are in the Sunshine State. A hundred out of 475.

African or Asian—a mix—and like many people and beasts, they mostly came south for the weather.

According to John Lehnhardt, Executive Director of the National Elephant Center (NEC) outside of Vero Beach, it is easier to keep the animals in a warmer locale because they do not have to be brought inside when the temperature approaches freezing. The elephants adjust because Florida more closely parallels their native tropical climates. And it doesn’t hurt that they have acquired a healthy taste for the Florida Valencia oranges that grow on the former citrus grove where the facility is located.

Writer and curator Sarah Sulistio talks to L.A.-based artist Harriet “Harry” Dodge about his video practice and participation in the upcoming biennial Made in L.A. 2014 (June 15 – September 7, 2014) at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. Harry Dodge’s video Unkillable (2011) is featured in Video Container: Touch Cinema at the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami (May 15 – July 6, 2014), organized by Sulistio. This interview was conducted over email.

If you maintain even a slight interest in humanity or, at least, have a keen set of eyes, you might’ve stumbled upon notes or photos or objects set adrift from their rightful owners. Grocery lists, unsent notes, half-torn documents, withered and aged photographs: in thrift stores or on the Metrorail, they are abound—floating, fragmented pieces of the human fabric. Writer and founder of Found Magazine Davy Rothbart has shared these pieces of strangers’ lives for the past fifteen years.

Florida drives always take longer than they are supposed to. We took the back roads to Venus from Miami and paid two hundred dollars for what Jacque Fresco refers to as a brain enema. At the end of the drive there were two guys from Toronto wearing yoga pants, a Pittsburgh pair, one with a furry beard, the other with fur boots, one milky white youngster from Copenhagen, and a statuesque couple with hardly identifiable accents. We were greeted by a man with a ponytail who opened a large gate that read The Venus Project. Suddenly, a compound of dome-homes (perfect for withstanding hurricanes), lush non-native greenery, hungry raccoons, and one sleepy alligator surrounded us as we made awkward introductions.

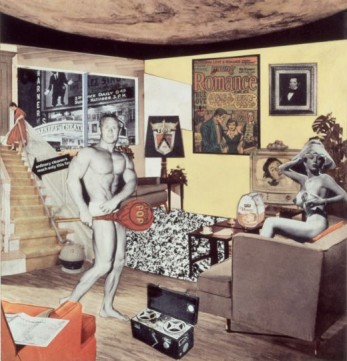

Richard Hamilton famously claimed that for him, Braun’s industrial design was as inspirational as Mont Sainte-Victoire was for Paul Cézanne. The sleek modern lines of Braun’s eponymous toasters were his phenomenological muses. This analogy provides great insight into Hamilton’s eclectic body of work.

Gravity and Grace holds satisfying contradictions: huge, humble; shimmer, trash; detail, big picture; spectacle, substance; industrial, craft. The scale of the monumental wall works is impressive, and the recycled materials they are constructed out of, curious. Like a magpie or a family of raccoons, we indulge in the multitudes of flattened metal scraps—bottle caps, tin-can lids—that comprise the works, and marvel at the mind-numbing labor required to produce them.

The tumble of first impressions went something like this: Street photographs. Striking colors. Not that large. In-your-face portraits—faces that looked as worn-out as old rugs, others full of confidence and a beauty rendered more intense by the way that what they were confident of was that the beauty wouldn’t last, so that the confidence too was touched by resignation.

The title of the group exhibition at David Castillo Gallery, Metabolic Bodies, implies that the strategy of using manipulated readymades is a corporeal action, a chemical change that transforms a substance (in this case found images or objects) into energy.

Reflecting television’s ability to both mirror and influence America’s middle class, in 1957 Lucy and Ricky Ricardo moved from Manhattan, where they had lived since 1951, to the suburbs. Rob and Laurie Petrie arrived in 1961, Samantha and Darren Stevens in 1964, Michael and Carol Brady in 1969. Helen and Morty Seinfeld moved there in 1989, but its unlikely their son Jerry or his pals are leaving the city anytime soon.

For all its regular crowd of artists and writers and creative hangers-on, the porch still isn’t Soho, or Greenwich Village, or even Coconut Grove. But it isn’t Hialeah, either.

The high-fives break out instantaneously like a saloon brawl.

Five dollar bill in front of the Kwik-Stop.

Surprise party patrons in paper hats crouching

underneath the dinette set. Spider web.

Bubble wrap. Kick-ass. Apollo pulling the stink of the night away

from his V-8 supercharged chariot. The stimulus check

comes in the mail! The stimulus check is cashed!

The work of Russell Maltz hovers in the fragile beats between two frequencies. One is the mark-making impulse of the human, while the other is the homogenous system of distribution of the inhuman. In his assemblages of generic building materials—concrete masonry units (cmu), metal studs, PVC pipes, and plywood—there are actions and operations rather than conceptual compositions. Thus the show title situates Maltz’s work as neither self-consciously elevated nor counterproductive.

In 1909 the Italian poet (and consummate self-publicist) Filippo Tommaso Marinetti introduced Italian Futurism to an international audience, through the publication of his first Futurist manifesto on the front page of leading Parisian newspaper La Figaro. Launched into the heart of the art world, Marinetti’s manifesto promoted Futurism as a new art borne of violent struggle, explicitly rejecting Italy’s status as the center for art of the past, with phrases such as “Set fire to the library shelves!”

Jenelle Porter is the Mannion Family Senior Curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, where she is currently organizing Fiber: Sculpture 1960 – present (October 1, 2014 – January 4, 2015). She spoke at Locust Projects on April 23rd. Soon after, she sat down with The Miami Rail to discuss craft, curating, and Boston.

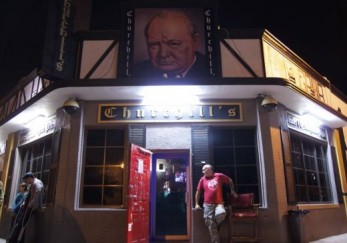

If museums are places where art goes to die, then Churchill’s is the place where art goes to get sloppy drunk, make a loud, hostile scene, and end up akimbo under a table, staring into its dark, gum-ridden underside. Then die.

A marking moment in art history, Biennial 2014 is the Whitney Museum of Art’s 77th and final showcase of American art in the storied Marcel Breuer building before surrendering it to the Metropolitan Museum and relocating to the Meatpacking district downtown. Essentially a last hurrah, this effortful production manifests the exuberance of a party girl; with a few quiet exceptions, the overall presentation is in your face, dressed to kill, and having a very good time.

Dawn Kasper is an American bricoleur: comic, aleatoric composer, environment sculptor, nomad. Since 2008, her mobile art practice has taken residence in a series of contemporary art spaces, from L.A.’s Honor Fraser gallery, to the 2012 Whitney Museum Biennial, where she could be found, making art, amidst the entire contents of her studio, installed into the third floor. Most recently, she built a temporary studio for the duration of a month at downtown Miami’s Cannonball Residency, which culminated in a performance on March 1st.

Christian and I dropped acid

at beautiful Scott’s wedding, all eyes

taking in light and shadow of bride and groom,

entwined tongues reaping applause from Old World grandmothers,

Christian teetering, red-browed

as he slid the garter up a 16-year-old’s thigh (more applause).

The Love Song of R. Buckminster Fuller: Review + Interviews with Sam Green and Ira Kaplan

Kevin Arrow

I was raised in the optimistic yet dark 1960s. I still have early memories of Buckminster Fuller and his counterculture-endorsed idealistic worldview. I remember my older brother’s first edition copy of the Whole Earth Catalog; I remember the radical “back to the land” advertisements for Mongolian Yurts, homemade yogurt recipes and essays on the I Ching.

This text could not start in any other way than by emphasizing how the following words are produced by my own subjectivity and built upon a single trip to Miami. Beyond the metaphorical aspect of the cities we visit being islands in an unknown sea, the map (pg. 37) gives the reader, who is likely to know Miami in a much better way than I do, an overview of the neighborhoods that I experienced when I was there.