George Sánchez-Calderón, “La Bendición,” 2001–2003. Photos courtesy the artist.

Early on, Sánchez-Calderón displayed found objects atop hefty soapboxes of identity and social politics. Guayaberas, the iconic Cuban shirts, were cast in aluminum and iron for “Cuban Armor” (1994–1996). In 2001, however, he purchased the building that became The Bakery, his studio and home beneath I-395 in Overtown. Moving to the city’s vacant epicenter proved transformative; his work increased in scale and ambition just as the Miami art scene slipped into international focus. Specifically, the move provided thematic ammunition for a sustained attack on the master builders of the twentieth century — men like Le Corbusier, Robert Moses, and President Eisenhower — who Sánchez-Calderón came to see as a few shades from criminal.

George Sánchez-Calderón, “La Bendición,” 2001–2003. Photos courtesy the artist.

But as the ambition of the work increased, so did the logistical difficulty. For “The Family of Man” (2011), which was on display at the de la Cruz Collection, George bought the old train sign from Boston’s South Station on Ebay for $350. Getting the 1.75 ton sign down the East Coast cost over 10 times as much. TOMORROWLAND, a project space that Sánchez-Calderón operated through 2011, was a welcome addition to the Miami gallery circuit. But its rough location required cooperation with a slumlord and paying half of the neighborhood to keep the other half from bothering visitors.

Like Christo with a nicer tan, Sánchez-Calderón’s true medium became red tape. Unfortunately, it began to tighten around his home in 2009 when he drew up plans to renovate The Bakery. A second story would be built, and an amphitheatre would allow guests to gaze upon the Biscayne Wall — the shimmering quartet of oversized condos in Downtown. On the top was a 60-foot billboard that Sánchez-Calderón thought would be a revenue generator but ended up as the project’s undoing. In order to comply with the City of Miami’s sign ordinance, which states that only national companies can hold sign permits, he had to sign a contract with Amherst Media Investors. He says they assured him that he would be able to expand his building, and that they would even finance the renovations. But in the end, the deal fell through, and the permits for expansion weren’t approved based on a disputed 10-foot variance on the property. George claims this is because his attorney was pressured by Amherst to file the permits incorrectly.

This incident is a perfect corollary to his artistic practice, which attempts to balance bureaucratic migraines and a heartfelt, if somewhat unbelievable humanism. To add to his problems, FDOT is trying very hard to “put an exit ramp through the living room.” The move is part of the planned revitalization of Downtown, a Pyrrhic victory for many living in this part of the city. Sánchez-Calderón traces blame back through Eisenhower, with whom the artist shares a birthday and whose administration was behind the Federal-Aid National Highway Act of 1956. From there, he indicts city planners — William Levitt, Robert Moses, even Baron Haussmann, whose plans for Paris were first and foremost a political move. The narrow cobblestone streets were too easy to barricade.

“Nobody thinks of the highways as anti-protest,” Sánchez-Calderón continues, his mind reeling back through history. “Hitler clearly made the autobahn to land planes on.” But although change is in the wind, the area surrounding his studio remains a ghost town, and George is free to play host to a revolving group of artists and passersby. “I paella a lot,” he says, revealing not a flawed bilingualism, but something more ontologically pervasive in Miami. Here, actions stagnate to the point where they become nouns; and people, places, and things are never quite where you left them. It is in this maddening struggle that Sánchez-Calderón has inadvertently created his gesamtkunstwerk. He has come full circle, replacing the found objects of his early years with an entire network of clogged highways and vacant city blocks, all smothered in paperwork.

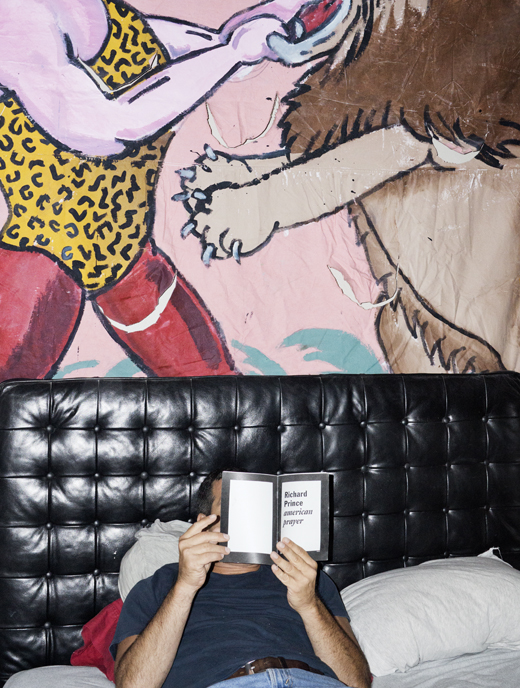

George Sánchez-Calderón reading in his studio. Photo courtesy of

Gideon Barnett.