With her Paper Folding Series, Odalis Valdivieso uses the relatively new and quickly-evolving trajectory of digital photography against itself. The self-destruction is, however, in a well-composed guise. It is difficult to view these pieces as self-destructive because Valdivieso creates moments of nostalgia for Modernist aesthetics through a combination of image capturing, printing, cutting, painting, re-scanning, and digital manipulation.

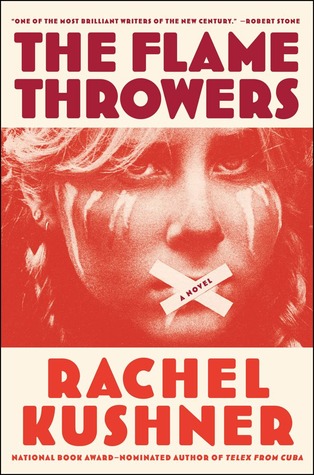

“I come from reckless, unsentimental people.” Thatʼs Reno, 22-year-old motorcycle-racing art-school graduate and heroine of The Flamethrowers, Rachel Kushnerʼs brainy, provocative, and bristling follow-up to her National Book Award-finalist debut, Telex from Cuba. The year is 1976.

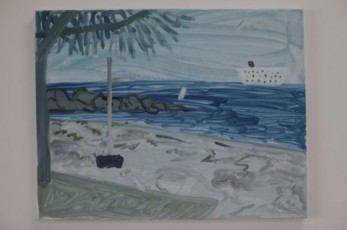

For two weeks this January, Chicago-based painter Tyson Reeder took his practice en plein air to South Florida. The carefree, playful act of painting on Miami’s beaches contained just the sort of atypical ingredients you would expect from an artist who has orchestrated art fairs in bowling alleys and in the dark.

Though steeped in similar conceptual concerns, McElheny’s film, The Light Club of Vizcaya: A Women’s Picture, lacks the aesthetic and seduction central to his widely-recognized installations. Incorporating meticulously hand-blown glass, the sculptures appropriate Modernist design and art objects, fraught and progressive at once, that propose a new world using often-impossible models.

For his new show, Daniel Milewski takes the down-home objecthood of Americana and launches it into the nebulousness of pop cultural trivia, art historical references, and the artist’s own sentimental education. If there was ever a time to imagine some kind of union between Ted Nugent and Sophie Calle, as filmed by Cameron Crowe, it would be now.

The first thing one has to ask is whether personal selection isn’t the most reactionary form of engagement with the concept of labor and the complexity of its descriptions. In the video, the invited parties justify their choices by alluding to family history, by comparing railway workers to 9/11 first responders, by reading religious and mythological references in the poses of the laborers depicted, by relating stories of provenance, and by drawing art historical correspondences.

Another part of the enjoyable puzzle of spending time with Price’s sculptures is wondering how the artist worked his fingers, hands, and even arms inside them. “Sourpuss” (2002), for instance, one of the sculptures on loan from Gehry’s own collection, is a mold- and rust-colored ghost of sweeping, bulbous forms.

The Miami Art Museum, en route to a better home and hanging gardens, has staged a love letter to the city as its final show in the old place, an epistle both endearing and sly. Meet the Miami we all know—its flashy environment, natural and built; its hidden narratives, historical and current; its backstories, real and imagined; its ready-mades, and its artifice.

Magical times have perhaps waned, and hopes for a real dragon would be absurd, but the children need some sort of payoff. The circus is in town. Specifically, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey presents “Dragons.”

Xuxa is considered the most popular beautiful superstar woman in Brazil to have her own line of children’s shoes. Some believe she made a satanic pact to appear on TV in giraffe suits and pink spaceships. Today, her special musical guest from Liberty City is the Bass Mechanic. She is Shoo-sha. He is A.D.E. She once declined an offer to be the mother of Michael Jackson’s baby. He once threw a cheeseburger at a bus. She had a breakfast song called “Who Wants A Bread Roll?” He could do the “Tootsie Roll” but probably wouldn’t admit it. She was nearly kidnapped in Rio. He was nearly killed in Rio. We could go on. The tape is still rolling.

Olvido García Valdes has published a number of books of poems. An anthology of her work, Racines d’ombre, has been translated into French by Jean Yves Bériou and Martine Joulia and published in 2010. Poesía reunida (1982-2008) brings together her collected poems.

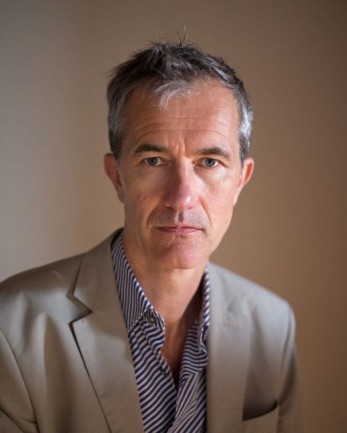

With last year’s publication of Zona, his book on Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker, Geoff Dyer has further established himself as someone who can write about just anything. His subjects have included the Venice Biennale, Jacques Henri Lartigue, Burning Man, and World War I statuary. Here, he talks to Hunter Braithwaite about boredom, a writer’s youth, and “inhaling the dead.”

Jillian Mayer is a real estate agent on Second Life—she manages the sales of online parcels of land you can’t touch, a daunting task. And like the Internet at large, her work is similarly ethereal, straddling the line between the physical and a vast unconsciousness, best understood by a member of a generation that lived through Brian Eno’s Windows 95 theme and Oregon Trail on boxy IBMs.

Creative Time President and Artistic Director Anne Pasternak and Bass Museum of Art Executive Director and Chief Curator Silvia Cubiñá discuss issues and implications of public art.

The idea came from a very selfish position to empower artists in a remarkable literal sense, by inviting them to take a day to curate an exhibition. The opportunity would allow artists to perform and create projects they could not do in another architectural space.

In kissing, the action is really on the inside—felt rather than seen—experienced only by the two engaged in it. One could even say then that kissing structurally resists visual representation, making the story of kissing in art particularly interesting.

There’s a large two-story house just north of 36th Street on the borders of Little Haiti and the Design District painted Port-Au-Prince baby blue and surrounded by unruly bougainvillea, morning glory vines, and empty cognac bottles. The downstairs has been claustrophobic since the windows were covered with concrete; the wood floors have gone scuffed and scratched and a steep, groaning staircase leads to the rooms on the second floor.

But on Duval Street, the pulsing artery of the tourist’s Key West, slantwise across the street from an open-air bar where not a minute of the day passes without the accompaniment of live acoustic guitar, are the towering wooden doors of the San Carlos Institute.