- The State of the Book: Antonia Wright and Ruben Millares

- John Baldessari: Installation Work 1987-1989

Eve Sussman: Rufus Corporation

Laura Randall

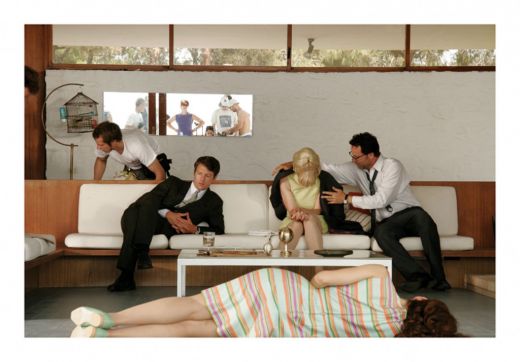

Eve Sussman, Marilisa on the Floor, 2005, Digital C–print, 39 1/2 x 51 inches. Private collection Richard J. Massey

The Bass Museum

By Laura Randall

Eve Sussman’s video installations at the Bass Museum of Art consider two canonical moments in art history. The films examine Diego Velázquez’s “Las Meninas” (1656) and the story of the Rape of the Sabine Women, refashioned through a contemporary artistic lens. Sussman’s video projection, “89 Seconds at Alcazar” (2004), offers a 10-minute imaginary glimpse inside the Spanish painter’s courtly world. Sussman’s later work “The Rape of the Sabine Women” (2006), which draws heavily from Jacques Louis David’s 1799 version, presents a modern adaptation of the mythical founding of Rome.

Sussman’s video, “89 Seconds at Alcazar,” garnered much praise during its original run at the 2004 Whitney Biennial. Set in the enigmatic hall where the artist captured Phillip IV’s royal family, Sussman’s characters move delicately about the room, exchanging inaudible whispers muffled by the crackling wooden floor and rustling of elaborate costumes. By summoning the power of the highly approbated painting, the film harnesses the familiar sensorial pleasures of its originator. Outside of the gallery echoing Spain’s emblematic past, Sussman demonstrates a greater willingness to think within the present, though not without some resistance.

Sussman’s “Rape of the Sabine Women” is a break up of her 80-minute operatic film now projecting simultaneously in five acts at the Bass Museum. Her version of the tale transports Rome’s mythical history to an era loosely set in the 1960s with scenes that recall the neoclassical formula of Jacques-Louis David. The tale suggests that Rome was founded by two brothers, who in order to populate their new city, abducted women from the Sabine tribe, igniting a series of wars between the two tribes. Act I is set in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum, a site that houses one of the best preserved Greek monuments, for which the museum is titled. Romulus and Remus appear here as two handsome young men. Anachronistic elements are interspersed throughout the modern setting. In Act I, the pristine architecture of the Pergamon Museum, designed to complement its Greek treasure, works much like the high-fashion suits shrouding Rome’s ancient heroes. A wolf strolls past Romulus at Tempelhof Airport’s baggage claim in Act II, a clear reference to the she-wolf who nurtured Rome’s legendary brothers. As the scenes shift, the film morphs from black and white to color, from clear, bright screens to grainy dull stills on old rear projection TVs. The narrative comes to a head when the brothers enter a crowded meat market where they conduct their kidnappings. Act IV is projected on a four-walled double-sided screen conceived as a patio structure, mimicking the chic suburban setting within the film. The Sabine women appear as glamorous socialites basking in a modern Mediterranean home. The battle scene in Act V is transposed onto a clustered group of televisions at the end of the gallery. The heap of besmirched bodies in the throes of their coup de grâce move on screen with the stillness of a tableau vivant.

For the painter David, “Abduction of the Sabine Women” demonstrated a concern for a social body that was traumatized and fractured during the Terror. The character central to David’s painting is not hero, but heroine, torn between the love for her new husband and her kin; her position in the painting is central, arms outstretched between the opposing sides. The characters in Sussman’s Sabine assume gendered roles that articulate problems of a modern world and lack agency. The women in Sussman’s beach house appear sedated, and anti-heroic in battle. Sussman’s “Rape of the Sabine Women” instantiates a cultural moment of the 1960s as gender disparities became more prominent in the social discourse. Sussman achieves this visually through the implementation of genre, namely history, as a tool for translating the values and ideals of a society, especially concerning the role of women. By addressing moments in Spain’s past that continue to challenge today’s viewers, and a not so distant history in her version of “Rape of the Sabine Women,” Sussman’s projects waver between cultural myth and realism as capriciously as the stylistic pattern of her film.