Caribbean: Crossroads of the World

Janet Batet

Tam Joseph, Spirit of the Carnival (The British forces of law and order in confrontation with an ancient African Spirit), 1982. Acrylic on paper, 78- 3/4 x 78-3/4”. Courtesy of the artist © Tam Joseph.

Pérez Art Museum Miami: April 18 – August 17, 2014

The Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM), with its landmark architecture inspired by Stiltsville, tropical flora, and its keynote waterfront view, emerges as the natural host for Caribbean: Crossroads of the World. The exhibition, which originated in New York City in 2012,[1] has adapted very well to its new venue by reducing the number of works, adjusting the thematic subgroups that support the show, and emphasizing cultural groups from the Caribbean area with a strong presence in South Florida.

Caribbean: Crossroads of the World, offering a 200-year survey of visual culture from the Caribbean Basin, results from more than a decade of devoted work by curator Elvis Fuentes. Taking as its point of departure the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804)— a pivotal moment that changed the Caribbean’s dynamics with Europe—in the history of the area, the exhibition rejects the reductionist and extended chronological vision of a place where the coexistence, persistence, and overlap of different historic eras is one of the most outstanding endogenous characteristic.

José Bedia El caldero: un recipiente (xx), 1984. 3 sheets, charcoal, and pencil on paper. 30 x 20 inches (each). Collection Pérez Art Museum Miami, gift of Peter Menéndez.

Four thematic lines guide the viewer through the show’s structure, the backbone of the exhibition: “Fluid Motions,” “Shades of History,” “Counterpoints,” and “Kingdoms of this World.” The pervasive presence of water acts as the leitmotif in “Fluid Motion,” the line that introduces the viewer to the show. “Fluid Motion” encompasses several issues: myth, religion, economy, and social concerns innate to the area. Not only does the water act as a metaphorical resource bringing together the different countries bordering the Caribbean Sea—both the islands and the coastal-inland countries bathed by its waters— but as an underlying, yet essential, link to the notion of liquid modernity described by Zygmunt Bauman,[2] helping us to understand the meaning of the Caribbean space not as a physical enclave, but rather as a complex living socio-cultural basin.

In this regard, Fuentes explains: “We assume the Caribbean area as a cultural space. The entire Caribbean Basin has been contemplated in the show, including the Gulf of Mexico and the great rivers, the Orinoco and the Magdalena reaching the Caribbean Sea, and the Mississippi pouring into the Gulf of Mexico. And of course, the diaspora: Miami, New York, London, Paris.” Following this subgroup the viewer will find works by artists such as Marc Latamie, Julio Larraz, Frances Gallardo, Paul Ramírez Jonas, Regina José Galindo, Eduardo Gil, Joseph Nacius, David Pérez Karmadavis, Francisco Oller y Cestero, Marisa Tellería, Abelardo Rodríguez Urdaneta, Marina Gutiérrez, and Asilia Guillén.

“Shades of History,” the second theme in the show, traces the beginnings of self-awareness in the region. Here we find key historic works such as the delicate piece by Castera Bazile, “Petwo Ceremony Commemorating Kayiman Bwa,” (1950) which narrates the Bwa Kayiman ceremony during which was planned the first major slave uprising that would lead to the Haitian Revolution; or the early study of Victor Patricio de Landaluze, “Cimarrón luchando con perros cazadores” (Runaway Slave Fighting the Hunting Dogs), dated 1860. In this subgroup, the historic figure of the cimarrón (the maroon) introduces the concept of cultural cimarronaje (cultural) maroonage and transculturation,[3] both of them associated with the emergence of a new cultural identity for the area: el criollo, le creole, the maroon.

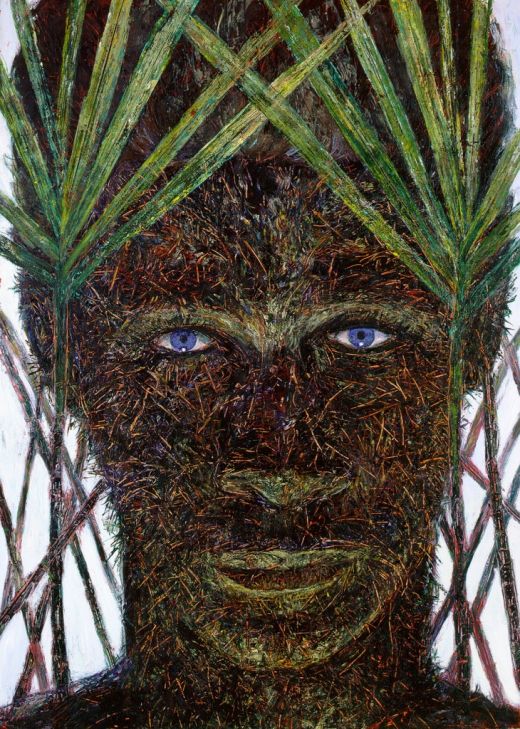

Arnaldo Roche-Rabell

Tenemos que soñar en azul (We Have to Dream in Blue), 1986. Oil on canvas. 84 x 60 inches. Collection of John T. Belk and Margarita Serapion Image courtesy of Walter Otero Gallery.

“Tenemos que soñar en azul” (We Have to Dream in Blue) (1986), a self-portrait by the Puerto Rican artist Arnaldo Roche Rabell shows a camouflaged face with deep blue eyes emerging from the sugar plantation. The piece, which focuses on Puerto Rican identity and Puerto Rico’s relationship with the United States, becomes also a symbol of Caribbean identity, subject of constant redefinition. The two last thematic subgroups (“Counterpoints” and “Kingdoms of this World”) focus on the area’s socio-economic changes and adjustments as well as Caribbean spirituality (its religions, music, carnival).

Dealing with the economy of the region, “Counterpoints” takes as its starting point the myth of El Dorado, that of the auriferous Caribbean characterized by conquest and colonization. “Disco” (Disc), (2003), by Aruban artist Ciro Abath is the perfect example. The golden token summarizes the stigma of a region born from the myth and desire of the conqueror. (Aruba means “gold” in Arawak.) One of the main interests in this section is to discard the extended notion of the plantation economy associated with the Caribbean. The Caribbean has changed a lot; the 20th century has seen the shift into a much more global economy linked to energy and tourism.

“Counterpoints” deals with the economy, both historic (plantation and slavery based economies) and contemporary (energy and tourism, essentially). This section of the show is supported by the thesis developed by Cuban anthropologist Fernando Ortiz in his essay “Contrapunteo cubano del tabaco y el azúcar” (Cuban Counterpoint: Tobacco and Sugar) that exposes the contrasting nature of the plantation system and tobacco industries.

“Sweet Island Cookie Cutters – Sweet Fuh So!” (2010-2012) by Annalee Davis (Barbados) plays with the notion of souvenirs to present a very critical piece. The installation is composed of several laser-engraved Andiroba wooden boxes that are carefully lined inside with artificial turf, the perfect manicured environment expected from the Caribbean. Each box contains a plastic cookie cutter shaped in the forms of different stereotypical motifs (golf, sailing, beaches, liquor) from that supposedly paradisiac destination: the Caribbean. “Sweet Island Cookie Cutters – Sweet Fuh So!” is an acute commentary on the changing economy in Barbados, and by extension in the Caribbean (from the sugar plantation to high-end tourism), the still-distorted vision of the region and changes in the economy that ultimately remain economies of social segregation.

The last theme, “Kingdoms of this World,” inspired by the paradigmatic novel by Alejo Carpentier[4], is a marvelous passage into Caribbean spirituality. Imbued by the multi-racial, multi-lingual, and multi cultural traits of the region, Caribbean religious beliefs and practices are very present in daily life, acting as inspiration and leitmotif for the arts. In this section, “The Jungle, by Wifredo Lam,” from the series “Stolen from MoMA” Pavel Acosta’s appropriation—a commissioned work for this show— not only restores the presence of the emblematic piece by Lam that the MoMA declined to lend for this exhibition, but also introduces crucial issues facing the region, such as the constant renegotiation of the Caribbean identity in the midst of the Post-Colonial era and the deconstruction-reconstitution, and cultural maroonage as surviving strategies of the Caribbean identity.

With over 180 pieces including paintings, sculptures, prints, photographs, installations, and videos, Caribbean: Crossroads of the World highlights PAMM’s commitment to the region, to our local community, and especially to artists from the Caribbean who reside in South Florida, such as Edouard Duval-Carrié, José Bedia, María Martínez-Cañas, Glexis Novoa, and Julio Larráz.

***

[1] Caribbean: Crossroads of the World was originally organized by El Museo del Barrio in conjunction with the Queens Museum of Art and the Studio Museum in Harlem, and presented at the three institutions in 2012. The iteration of the show now opened at PAMM was organized by Guest Curator Elvis Fuentes and coordinated by Associate Curator Diana Nawi with Curatorial Assistant Maria Elena Ortiz.

[2] Bauman, Zygmund. Liquid modernity. Cambridge Press, 2000.

[3] Transculturation is a term coined by Cuban anthropologist Fernando Ortiz to describe the phenomenon of merging and converging cultures. The term was introduced for the very first time on his speech “On the Phases of Transculturation,” made at Club Atenas in Havana, 1942.

[4] Carpentier, Alejo. El reino de este mundo. (The Kingdom of This World), 1949. In the preface to this work, Nobel Prize-winning Cuban novelist Alejo Carpentier introduces the term “lo real maravilloso” (“the marvelous real”), concept developed the same year on his essay Lo real maravilloso americano (On the Marvelous Real in America). “The marvelous begins to be unmistakably marvelous when it arises from an unexpected alteration of reality (the miracle), from a privileged revelation of reality an unaccustomed insight that is singularly favored by the unexpected richness of reality or an amplification of the scale and categories of reality perceived with particular intensity by virtue of an exaltation of the spirit that leads it to a kind of extreme state. To begin with, the phenomenon of the marvelous presupposes faith.” (Alejo Carpentier, On the Marvelous Real in America. Magical Realism. Ed. Zamora and Faris, p. 85-86)