Betty Woodman—CONTRO VERSIES CONTRO VERSIA: An inaccurate history of painting and ceramics

Hunter Braithwaite

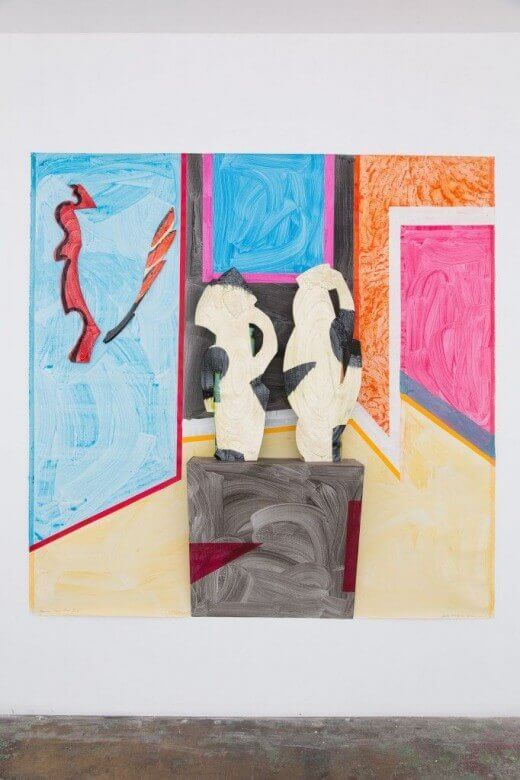

Betty Woodman, Finestra con Persiane, 2009. Glazed earthenware, canvas, acrylic paint. 84 x 84 x 15.75 in

December 2nd, 2013-January 11th, 2014

Flat or round, round or flat? At times, Betty Woodman seems like Magellan, sailing toward the edge, but sure that a curve will appear soon. For over half a century, the artist has explored ceramics’ boundaries and borders, not just the formal ones—as in how could this also be a painting?, but how the vessel reappears around the globe, from Italy to the Yucatan to Japan. The vase is the starting point, the destinations far flung.

Woodman, who has worked with the vase since she enrolled in Alfred University in 1948, has commented on its universal appeal, the fact that it has been used for millennia to contain everything from our wine to our ashes. But, she eschews its vaseness (excuse that awful word, I just mean that vases are primarily structures used to hold liquids, granular materials, or Gerbera daisies, and here they don’t hold those things), and instead breaks it down to a series of picture planes on which she paints.

Betty Woodman, Winged Vase: Pink Blush, 2009. Glazed earthenware, epoxy resin, lacquer and paint 36 x 20 x 11 in

To the vessel she affixes handles not meant for hands. Sculptural excursions, these are cut out of slabs of clay, bound by curvilinear edges that suggest wings, waves, or the undulations of a woodwind. Still, any grace is tempered by the urgency with which they are fused to the body of the vase. Woodman applies a day laborer’s seam of clay, a rheumatoidal juncture that matches the immediacy of the painted surface.

Perhaps she’s not interested in smoothing this down because on one level, the vases are meant to be shattered. Each vessel is broken up into views. This doesn’t negate their use value, but it amplifies the fact that a jug could (and should) be seen as a viable alternative to canvas. So although the pieces are painted in ways varying from patterned to figurative, the container is always present.

Woodman also reintegrates scraps leftover from the creation of her vessels into their final composition. Sometimes these scrap elements are strictly graphic. Other times they represent the pottery—often in a stark deployment of negative space—in absentia. The task for us is to decide whether to think of these as brush strokes or as shards. If we choose the former, we must confront painting. No problem, done. But if we choose the latter, we must then think of them in terms of time. Put another way, do they come before or after the vase? Do they testify to its construction or its destruction? That, along with the birth of curves, seems a most pressing question of universal import.

The exhibition is held in place by four wall-mounted pieces attached to painted canvas backdrops via unassuming and generic shelves. On the backdrops, the flattened space, ethereal blocks of color, and sure but irreverent linework all speak Matisse. Woodman places her vessels in a variety of painted contexts. “Double Vase, Double Window” (2010) and “Finestra con Persiane” (2009) both concern the domestic space (and thereby are closest to the French painter), whereas a work like “Museum View New York” (2012) has the vessels not on a table holding milk or flowers, but on a pedestal in a museum. Through the changing backdrops, we see that the contexts of vases are just as fluid as that which they often contain.

Betty Woodman, Museum View New York, 2012

Glazed earthenware, epoxy resin, lacquer, acrylic paint, canvas, wood

85 3/4 x 86 x 11 1/4 in