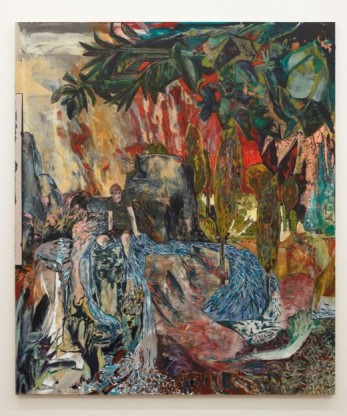

Hernan Bas has characters—boys. How he places these young men in their landscape is his conceptual project. A method of reusing and repurposing historical systems is devised to create a blueprint for the work, with identity politics, medium specificity, studio labor poetics, and market dependency all functioning as proof of its own language.

Charlie Smith has published seven novels and seven books of poems, has received countless awards, and has no Wikipedia page. If you Google him, you’re more likely to come across tales of another Charlie Smith—a man who claimed to be 137 years old when he died in 1979 (incidentally in central Florida). That Charlie Smith spent his later years telling his life story, all the while researchers tried to debunk it. This Charlie Smith is the 65-year-old author of the new novel Men in Miami Hotels, set primarily in Key West. In the early ‘90s, George Plimpton called him “a young William Faulkner.”

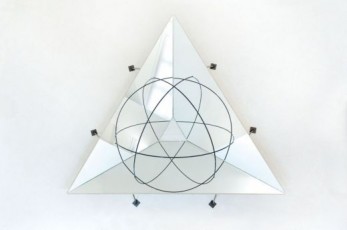

The navigability of a space is crucial to your experience in it. The way light enters and exits, how sound travels and how visitors are guided through all play into the functionality and aesthetics of a building designed around the sensory experience. The newly renamed and remodeled Emerson Dorsch Gallery’s co-owners and architectural collaborators clearly considered these factors and articulated a thoughtful, sleek new home inside the Wynwood warehouse they have occupied for over a decade.

It requires thousands of computers performing the same task to force a “take down,” footnoted in the exhibition’s press release as a “denial-of-service attack,” i.e, unavailable page. Yet, rather than an empty threat, the disintegration witnessed in the hallway was a partial re-staging of an artwork already present in the exhibition, “Anonymous vs Art” (2012-2013). A digital print on stretchers, the piece depicts screen shots as simple proof of successful momentary attacks performed against corporate art world websites, including tate.org.uk and davidzwirner.com.

Since 2008, the wulf. has been one of the pre-eminent venues for experimental music in Los Angeles. It’s housed, along with its two founders and directors Eric KM Clark and Michael Winter, in a downtown loft, which means that attending performances is a close-knit affair: the audience sits on dining room chairs, or couches, or on the floor, and there’s always a bottle of whiskey and bags of snacks on a table next to the bowl for cash donations. The wulf. is both a space and a community.

Where does a retrospective begin? Is it with the most recent piece in the show, as retrospection literally means to begin at the present moment and then retreat into the past, or does it begin with the earliest pieces—the scribbles and student work, those made before the artist hit his stride? Or, should one look through the pieces on display to find an exemplary work through which the entire career and life shines crystalline? When choosing a path to enter Arnold Mesches’s endlessly American oeuvre, one finds that the earliest work (1945) is an augury of all of the paintings to come, up until the last was picked up from the artist’s studio, still wet to the touch, in December 2012.

In the 1980s, Tyson was seen as both an animal and as a machine—the tenaciousness with which he trained, combined with the savage clockwork of his fights, produced a truly liminal man. Yet it was in the 1990s, when a series of controversies calcified to create a type of death mask of noble public figure. In other words—a celebrity. This extent of this evolution shown in the light of the screen, which featured his trademarked (this isn’t a figure of speech, ask the producers of The Hangover II) facial tattoo, looking like a decorative ninja knife mounted above some drug dealer’s flat screen.