ATHI-PATRA RUGA with Catherine Annie Hollingsworth

Catherine Annie Hollingsworth

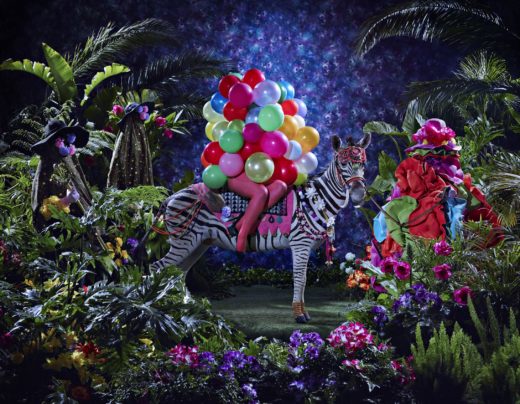

Athi-Patra Ruga, The Elder of Azania, 2014. Performance still, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Public Intimacy: Art and Other Ordinary Acts in South Africa. Photo: Geof Teague. Image courtesy Athi-Patra Ruga and WHATIFTHEWORLD

HOLLINGSWORTH (MIAMI RAIL): You started out in fashion, right?

RUGA: I studied fashion from 2002 until 2004 and did one or two collections. At the same time, I was performing in downtown Johannesburg in drag with a club kid crew. There was a movement between drag, clothes that I would make, and critical questions around the role of the fashion designer. The role of the fashion designer is that of entrenching gender behaviors and, at the same time, that of the social engineer. It somehow teaches one to parody the construct of femininity. All of this becomes a beautiful primordial soup that gives birth to my work.

RAIL: Can you describe the story you are creating with The Future White Women of Azania?

RUGA: At the end of 2009, I started doing processions. I’ve always found them powerful as an art medium, because they involve walking down the street with a mass of people with the same goals and pains as you. It’s this nonverbal yet powerful communication, saying, “We’re all together, going to the same space together.” And for me, being an urbanite, as someone who lives in chat rooms and on the Internet, I find that there isn’t much inter-human empathy. I also went back to the idea of parodying femininity. I created the characters with those balloons because I wanted to put a question or hypothesis in someone’s mind. The word “Azania” was used by postcolonial liberation movements to represent a utopian, decolonized Africa. I use the body of the white women to enter that future space and see what happens.

At the same time, I wanted to raise the forgotten history of the word “Azania.” Azania is first mentioned in written form with Pliny the Elder around about 40 AD, in a travelogue called The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. It was really interesting to know that my history did not start with slavery, colonialism, or the end of apartheid, because history books are always written by the victor and somehow negate what happens before. Precolonial history became something about rocks and all of that, rather than the existence of people.

The big storyline that I’m working with is that of a nation. I’m starting my own cardboard or balloon soldier nation of these characters that go through the catharsis of popping. They reveal themselves as both male, female, everything they are under those balloons. In the beginning, I used to put liquid in the balloons. And this would weigh a person down. Someone on the outside is looking at the fanfare, the flourish of balloons. Inside, the actual performer is struggling with this identity. So the performance itself is about embodiment, really.

Athi-Patra Ruga, The Elder of Azania, 2016. Performance still, Bass Museum of Art, Athi-Patra Ruga at bassX. Image courtesy Athi-Patra Ruga and Jorge Grouper

RAIL: So Azania is a concept that you grew up with, as part of the national conversation?

RUGA: Yes, it was part of the revolution-ary conversation, because my parents were the generation of Soweto 1976 [the Soweto uprising], a young generation that wanted to change things. The word “Azania” was used in this utopian sense: let’s return to this precolonial, beautiful place where freedom reigns, where we are not touched by colonialism and subjugation. I’ve grown up always knowing that my parents, and the parents before that, worked toward that idea. We are the people eating that fruit. However, there are hypocrisies that come with the genera-tions that are eating the fruits of freedom. Nobody gave us a manual for it; trust me.

RAIL: Most of the characters you create are political figures of some form or another. Who is your most recent character?

RUGA: I’ve started assuming the character of The Elder, the narrator. In this population of women, I’m the only male. I’ve been held hostage so that I can carry old and new stories. I can create this new government from exile with the Future White Women. It’s me finding the art-historical purpose of the male always making himself the elder or the narrator. On one side, I’m perpetuating something, but on the other side, I’m parodying it to bring attention to art history, how it’s relayed—and the power within that.

RAIL: What new projects are coming up for you?

RUGA: I will be in New York [at Performa] for a very cool performance, and then in Denmark I’ll be performing the next progression from The Elder. The Decimation is our next step of the nation-building thing, whereby we are killing ten people and hanging them from trees—ten balloon characters that look like piñatas. We invite the audience to beat the piñatas open. It starts out fun, but once you realize it’s looking like you are beating up people because the balloons are popping, you hope that the audience throws away their canes and goes, “Aaah! I’ve just committed genocide!” Or something.

RAIL: So you’re going right into the land of the colonizers.

RUGA: I call it counter-penetration; I’m very aware of that. I’m aware of the fact that I’m coming in as a way of reflecting these stories of belonging and movement and not belonging. I know that Europe at the moment is faced with its human-ity. I think all these countries are being faced with who belongs where, and what belongs where, and who defines them-selves as what.

Athi-Patra Ruga, The Future White Woman of Azania 1, 2012. Lightjet print, 80 x 120 cm, edition of 5 + 3 AP. Photo: Hayden Phipps. Image courtesy Athi-Patra Ruga and WHATIFTHEWORLD

RAIL: Race is a huge issue right now in the US, and it seems largely to be an identity crisis.

RUGA: In my personal experience, xenophobia is growing in Europe. It’s xenophobia, but it’s racism. South Africa experiences a lot of xenophobic attacks against our brothers who come in from various spaces, from Zimbabwe or from Zambia, because we’re the land of milk and honey for the south. So I always see how belonging and not belonging work in all the centers that I go to. And it always comes to one story. That’s why the universality will always be there. The purpose of art, for me, is to make people feel that it’s okay to feel the emotions of not belonging—hence the characters are very freakish-looking—and to come to terms with the idea that utopia really doesn’t exist. The only way I can say that is not by standing on a soapbox and shouting it. I have to do it in a very acces-sible, Trojan-horse kind of way.

Athi-Patra Ruga, The Elder of Azania, 2016. Performance still, Bass Museum of Art, Athi-Patra Ruga at bassX. Image courtesy Athi-Patra Ruga and Jorge Grouper

RAIL: What kind of performers did you work with in Miami?

RUGA: There were professionals, novices, high sorts of Pavlovas, and performance artists. Aside from the high discipline, you get performance artists who attack movement from a political position and are open to a subversive play, a chain reaction to the classical guys. And then it also moves down to the novices, mimes, people who can use their hands, work with another kind of registry, and continue the story. I love confusing highbrow and lowbrow. This is also a subversive nod to the sort of old, white, educational men who want to write art history and who I feel I’m in a very heated conversation with—with my body and the performers’ bodies.

RAIL: It’s perfect that your Miami performance took place in the library, which is a very open place.

RUGA: I started out with that, you see? In the club kid scene, you’re performing for people in the street, so they don’t eat you up on the way home. You’re performing for mere survival. The library offered me a place where everybody could come in. I was really surprised about how welcoming it is to people in the streets, even just on the basic sanitary level. I was so pleased to be performing in a space that doesn’t have a velvet rope. Because whether it’s queer politics or black politics or woman politics, they aren’t supposed to be put out to an audience that just nods, “oh great,” and then moves on to their canapés. It’s for people who are going to be haunted, and who are going to relate to the stories.

Catherine Annie Hollingsworth is a Miami-based dance and performance writer.