Flush Times: Marquee Magazine and Miami of the ‘80s

Nathaniel Sandler

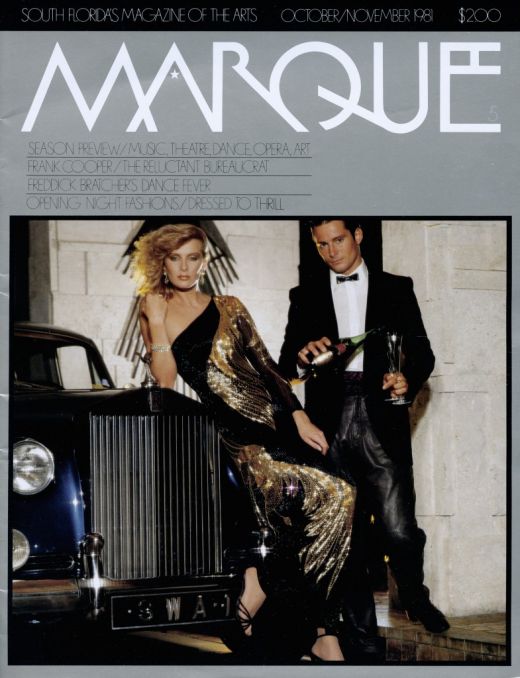

Marquee Magazine's October/November 1981 Issue.

–Mark Twain

Mark Twain was born in Florida—a now abandoned village in Missouri called Florida, but Florida nonetheless. His family moved away from the sleepy and sparse township when young Samuel Longhorne was only four. The town of Florida, apparently, did not have much to do.

Twain spent his life documenting things in this country. Actions, inactions, the drives and fancies of men, all now sewn sturdily into the narrative of these United States through his storied life and work. Yet, Florida, the state, falls mostly outside of the canonical narrative of America. Many schoolchildren who grow up here are not taught local history.

The quote above, from Roughing It (1872), relates to Twain’s vision of the gold prospecting towns of the Wild West, but it could just as easily relate to Miami. There are many points in time where we could look back on the oft-scattershot history of high rises and mangroves and speak of the same sort of flush times that Twain captures. From the 2008 real estate bubble backwards, to the land boom of the 1920s, Miami’s economy has plumped and ripped open so many times it’s become what we all expect.

But the birth of the literary paper. That is unexpected.

In 1980, Leonard Abess started Marquee magazine on Miami Beach because, on his own admission, he “wasn’t really doing anything.” A friend of his, named Bill Bucola, had inked an agreement with many of the local arts organizations to merge their newsletter. The main ingredients of an artistic-city stew were all in place and yearning for collective growth—the ballet, the symphony, the opera, the playhouse. Some are even still named the same today.

All that was needed was someone to provide the words. The magazine set out to be a newsletter but changed into something different quite quickly, its glossy pages incorporating short and long-form articles highlighting the local arts and culture scene. Marquee was not without its initial growing pains. The various arts organizations that had previously agreed to marry their newsletter all refused to share their proprietary mailing lists. The worry was the mailings would end up duplicated if the same person had signed up for multiple lists. Abess says that his friend ended up getting 27 copies of one issue delivered to his door. He goes on to explain that, “you think you have 35,000 addresses, but you’ve really got around 3,700.” This is how small the arts scene in Miami was in 1980, with not even 4,000 composite addresses of arts patrons spread across the major organizations.

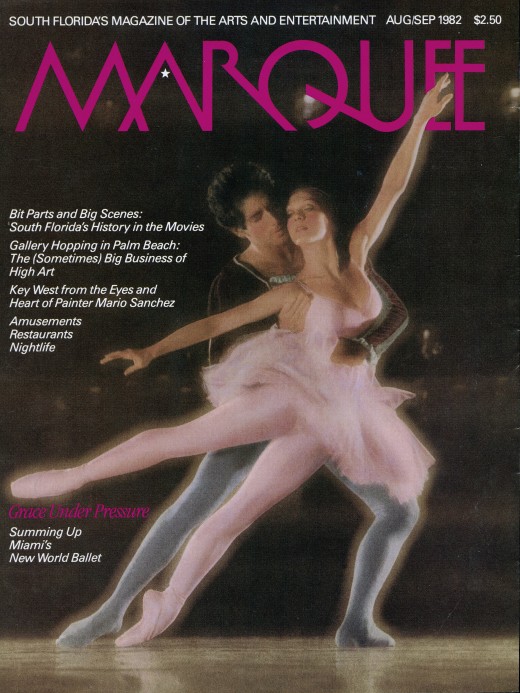

South Florida’s Magazine of the Arts’ August/September 1982 issue.

Called the names that now people in South Florida only hope to lay claim—the “King of South Beach,” or the “Unofficial Mayor of Miami Beach”—Canales lays no stakes to these titles despite having opened around 45 venues including nightclubs, bars, restaurants, hotels. In the mid-‘80s, he started seeding the city with the types of party and leisure spaces that now make up the backbone of Miami’s economy. He speaks of the era reverentially, a time when “it was authentic, the energy was real.” He was attracted to the spirit that took risks on public art commissions by Christo and Claus Oldenburg and his venues hoped to capitalize on the New Yorkers and fashion scene coming into town. Models by the droves pouting by the sand in this tropical blank slate of Miami, a sleepy haven to the elderly yearning for a fresh identity. Canales set about integrating music, lights, and art into the nightclub scene, which was all cutting edge at the time, and he firmly declares that in “everything I did I hired local artists.”

Canales moved to Miami on the tail end of Marquee’s run, when the publication was in full swing and producing content of award-winning quality. In 1982, an article written by Jack McClintock titled “On the Porch of the Cardozo Hotel” set a picturesque scene of the arts and literary scene in early-1980s Miami Beach. It positions the classic deco hotel as a sort of bohemian slosh of writers, artists, models, eccentrics and incredibly old people; it’s an enchanting read that recreates a singular moment of Miami’s history. Sitting on what would become some of the most expensive real estate in the world, the “porch rats,” as the writers and artists of the Cardozo were called, had a long running unofficial worst t-shirt competition and never knew if the espresso machine would work that day. McClintock describes the characters that spotted the setting such as, “The Haunted Hindu,” “Electric Bob,” and “The Woman Who Has Not Discovered The Wheel (so named because she tows belongings along the sidewalk in a cardboard box),” amongst others who weave in and out of the Cardozo.

It was a Miami Bohemia, a reality that Wynwood only scratched at before proficiently hurtling past today’s underpaid staples of the creative class. Experimental sound composer Gustavo Matamoros who was (and still is) living and working in Miami thinks, “something was happening then that I believe fell through the cracks only because it was covered not in the New York Times.” It’s a common byproduct of nostalgia, those good old days, in which everyone looks back on the times when they were youthful, vigorous and had the world in front of them. But the sense that it somehow went undocumented or missed by the rest of the country is palpable. The energy though is something many speak of. There was some sense amongst the few artists creating work in Miami that since it wasn’t watching, the world might have actually been there for the taking in the early- to mid-1980s.

David Vance, a fashion photographer whose work was often featured in Marquee speaks about Miami during that time claiming, “there was everything. All the most creative people. The energy was intense. The possibilities were endless.” Vance photographed the models and the nightlife, such as Stephen Bauer who played Manny, Scarface’s sidekick on the big screen, and Alvin Ailey, without even knowing who he was.

Tom Austin, a writer whose work was regularly featured in Marquee has a slightly more realistic view of Miami at the time, suggesting it was more “like a village” than a city on the brink. It’s because of this, and the incredibly small talent pool, that a good deal of the visual and written content was purchased from other publications. Austin wrote a piece about the nascent nightclub scene at the time, which launched his career as a nightlife writer for years to come. He admits of Marquee that there has, “still been nothing like it ever. It’s incredible, it was all so smart, there were no attempts to dumb anything down and it was more intelligent than anything Miami has seen since.”

As you flip through Marquee from the first page to the last you can feel the rewarding growth of a composite project. The first issue comes across as a benign newsletter, a bulletin board of events and advertisements, but later issues start exploring issues relevant to the landscape in a way that you understand as important. Perhaps it’s hindsight, but sifting through the list of now dead galleries and classifieds for bulldozed condos, you feel like something was being built. There was an epic two-part South Florida film bibliography list, a masterful piece on the importance of local historic preservation, countless well written reviews of emerging and established Miami artists or the heavy hitting names brought into town. The writing got better with time. And that is surely because Leonard Abess often sat on that porch at the Cardozo. He says quite honestly that he, “fell in love with the artists,” and at times he would sit with them with “water guns and shoot at people when they walked by, but it wasn’t a big deal because hardly anybody walked by.”

So where did Marquee go? Abess gave up the magazine in 1984 because his career moved on, purchasing City National Bank and becoming an enormously successful and well-respected figure in Miami. While attempting to sell Marquee advertising to the Bal Harbour Shops, he met his wife Jayne, the PR Director. She refused to buy an ad, but said “yes” when Abess sheepishly returned inside to ask for a date. He was wearing red bell-bottoms. It was a different time.

Many of the writers and photographers moved on. Austin went to The Miami Herald, and Vance continues to live and take photos in town. Others dispersed throughout the United States. A few of the people contacted for this piece weren’t able or willing to remember much. Asking someone about a creative project they worked on 25 years ago is sometimes met with excitement but often with confounded apology. I’m sorry, I simply don’t remember.

Memory gets in the way, as does its lack. Rise and fall and try your damnedest to plateau at the right moment. Similar could be said of Miami, where the city’s reveling inhabitants as well as interested onlookers constantly feel the need for a clearly delineated trajectory. Setting out to create the narrative of a city, whether in hindsight, foresight, or catching some kind of current pulse is not an easy task. But this is what the writers, editors, and publishers did. They documented Miami and its cultural scene at a particular point in time that cultural tastemakers and mainstream news across America were largely ignoring.

Much of the rhetoric in the magazine reads like the blogs and think pieces of today. Miami was then a city of the future, brimming with possibility and delight in the future’s prospects. Abess, when referring to a particular article about the growth of downtown in Marquee, states “Miami is always growing and changing,” and goes on further to declare, “you could run that article anytime, going back to when I was six years old.“

And it’s true: Miami’s storyline is defined by a kind of stasis of potential. A Wild West of the tropics, that always feels the next railroad brings the exact combination of cityscape essentials. Some men and women and their pursuits rise and some fall, but Miami stays on the precipice of a self-imposed impending great ness. That is how, whether “flush times” or not, Miami continues. On both sides of the bay the cranes sprout and construct and move on to a new neighborhood, wherever the money, dreams, and fancy of Miamians who mold the concrete on top of swampland go.

Perhaps constantly reaching for the promise, becoming a “real” city is why Miami falls outside of the national narrative. The specter of promise looms constantly, like the cranes and like the next big thing that will somehow put the city on the metaphorical map. If New York is a gigantic apple, we are but the seeds, fertile and beautiful, yet constantly unrealized. And if you accept the growth potential without constantly talking about it then maybe you’ll find the mangrove is already there, beautiful, tangled, and wild.

It behooves mention that it would be incredibly unaware to avoid the conversation about another “literary paper” signifying “flush times.” May a brief and humble chronicle of The Miami Rail one day be written inspired by a quote from Twain and the radiant creativity of Miami.