Simon Starling

Hunter Braithwaite

Simon Starling, Inverted Retrograde Theme, USA (House for a Songbird) (1:5 scale models of No. 2 and No. 4 Calle Victoria, Villa Contessa, Bayamón, Puerto Rico designed in 1964 by Simon Schmiderer for the International Basic Economy Housing Corporation, USA, installed upside down to act as cages for songbirds), 2002. Wood, iron, mahogany, and soundtrack of songbirds. Collection Pérez Art Museum Miami, gift of Debra and Dennis Scholl.

Pérez Art Museum Miami

April 24 – September 14, 2014

I have limited experience with songbirds. When I lived in Munich as a small child, we went to visit four distant aunts who shared a small apartment in Kettwig. They had never married because all of the men had been killed. For company, they kept a little bird. This was the first time I saw a bird up close, teetering on a metal tube above a bramble of newspapers, and it was quite memorable, in more ways than one. See, years prior, this bird had been let out of his cage. It might have been the first time, or just one of many regular excursions. But that day, the first thing he did was stretch his wings, flutter up to the ceiling, and then swoop down across the room, right into a full pot of simmering stew. “Ploop” was how one of the sisters described it, her jowls ashuffle. So they scooped him out with a slotted spoon, set him on a paper towel, and waited. The bird survived, but the stew kept his feathers. When I saw him that day, he was completely bald, nothing more than a little kaiserscrotum.

There are no birds in Simon Starling’s two birdcages, feathered or not. There should be two, but there are none. The piece, Inverted Retrograde Theme, USA (House for a Songbird) (2012) is essentially a pair of large birdcages made out of wood and decorative iron grates and compressed against the ceiling by two mahogany trunks which erupt from the gallery floor. The title says they are houses, and they do look as such, but I insist on calling them birdcages. The difference between a birdcage and a birdhouse is that the latter has a door.

The birdcages look like homes because they are 1:5 scale replicas of two houses in Bayomon, Puerto Rico built by the modernist architect Simon Schmiderer. Like others in the neighborhood, they are based on geometric repetition, made out of concrete blocks, and designed to have open windows and doors. This openness cooled the homes, kept costs low, and integrated the private, domestic space with the communal and natural space outside. All fine and good when your communal space has no crime, but the increase of violence and theft in the ‘70s forced residents to bar their windows and doors—protecting themselves, but turning their home into a cage.

Schmiderer’s houses in Puerto Rico.

Starling’s original sculpture is a poem to the compromises we all make: freedom, safety, beauty, all that must be exchanged over the course of our lives. Modernism has long been criticized for ignoring the human (and animal) needs and desires of its subjects. Starling’s work, while quite difficult, pins this with the brutal precision of a lepidopterist’s needle. But by replacing the birds with a recording, we instead have a whimsical sidestep. The work becomes dust jacket image for a Maya Angelou book.

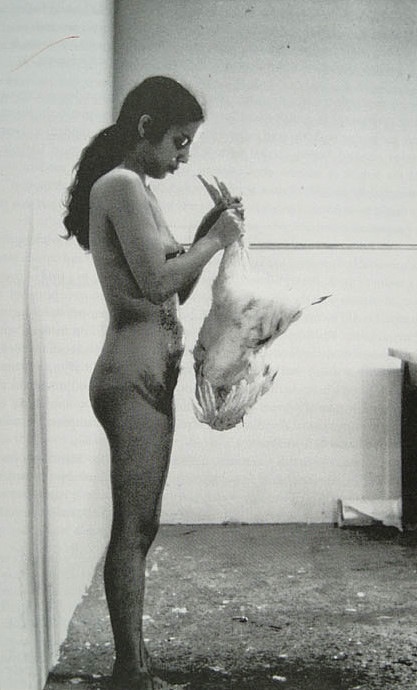

Ana Mendieta’s 1972 “Untitled (Death of a Chicken)” piece.

• Dead dead: Robert Rauschenberg’s Canyon, which includes the taxidermied body of an eagle.

• Dead: Joseph Beuys explaining pictures to a limp rabbit.

• Dying, quickly and messily: Ana Mendieta lobbing the head off of a chicken with an ax, and then holding its gushing corpse to her naked body.

• Alive, just chillin’: Darren Bader’s cats, which were allowed to roam a gallery at MOMA PS1, and were available for adoption; Pierre Huyghe’s dog, which got to spend the summer of 2012 prancing around Kassel.

• Alive, but isolated in a dark box in an air-conditioned room: Simon Starling’s birds.

And then, does the quality of the art matter? Many people are offended by Wim Delvoye’s practice of tattooing pigs. I am as well, but mainly because the work is so stupid. Does the species matter? The temperature of the gallery? All of these issues have bearing on the issue, but none are definitive. What is clear is that the use of animals crosses some kind of line. While it might test the limits of morality, it also moves past the limits of culture. They show us the edge of art. What it can’t do, where it can’t go. John Berger’s 1977 essay “Why look at Animals?” has a great sentence. “The animal scrutinizes [man] across a narrow abyss of non-comprehension.” No matter the relationship between art and animal, it is lost on them. And they, us.

Installation View of Darren Bader: Images at MoMA PS1 in 2012. Courtesy the artist and MoMA PS1.