- Philodendron: From Pan-Latin Exotic to American Modern

- A JOURNEY BETWEEN THE BOSPHORUS AND THE SEA OF MARMARA: Impressions from the Istanbul Biennial

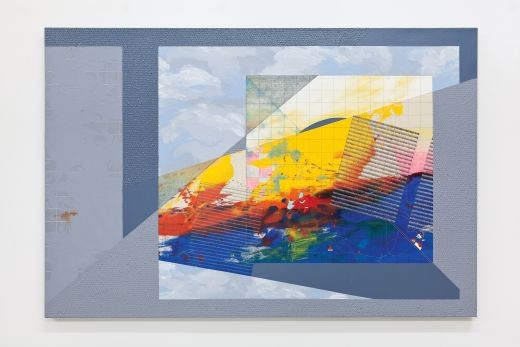

Robert Huff: 47 Years

Monica Uszerowicz

Robert Huff, Miami Windows/Miami, 1982. Pencil and acrylic on canvas, 121.9 x 182.9 cm. Photo: Francesco Casale/Letter16 Press

SEPTEMBER 4–NOVEMBER 8, 2015

“Teach your hands to see, and your eyes to feel,” a potter once told me. I’d wandered into a ceramics workshop at a flea market, and my unfamiliarity with the craft left me thinking of the phrase as advice intended for metaphorical applicability. That wasn’t really necessary—its simple meaning is special enough, especially in practice.

The late Robert Huff embodied this notion of the interchangeable nature of feeling and seeing, of working between disciplines to create something whole from seemingly disparate parts. His death in 2014 left behind a kind and incomparable legacy—as a sculpture professor at Miami Dade College and chairman of its art department, he inspired and worked with some of Miami’s best artists, integrating with the earliest incarnations of the city’s arts community itself. Huff’s retrospective at MDC Museum of Art + Design (MDC MOA+D) is actually surrounded by works he selected while helping the museum establish its collection; currently, MDC MOA+D is a matryoshka doll of a gallery, Huff’s influence increasing with each step throughout.

The artist and his family were involved in the construction business—he was a budding builder before he relocated from Kalamazoo, Michigan, to study at the University of South Florida. After receiving a degree in fine art, Huff remained a polymath, combining the tools of his former trade with his artistic practice: an arresting amalgamation of sculpture and painting.

And something else. All that pine and bronze, the pulleys and aluminum, display Huff’s love affair with structure and architectural form, the outline and feel of it, but also its capacity for mutability. There’s the trademark of someone who works sturdily with his hands permeating every piece, yet it’s fluid—playful. As a maker, Huff also happily dismantled and abstracted anew. He knew how to observe and rebuild his environment, but it’s more important that he was fascinated by it.

The landscapes he traversed, and the shape of the cities therein, feel ever-present. Clinch River (2012), an oriented strand board, is adorned with thick swaths of blue paint and sketched funnel shapes that recall smokestacks. Titan (2010), a towering pine maquette of a building, is gridlike—look through the slats and you’ll see bronze, steel, a city in miniature. The pulley in Pete’s Pulley(1996) consumes a wall, and is then swallowed by bright canvas on either side. We might be looking at landscapes each time—sky and steel, natural and oppressive—or something else entirely. The works’ individual parts meld together the way palm and cloud begin to sit comfortably alongside a well-lit skyline.

Tennis Match (1970), a set of colorful found objects arranged as delicately as the wiring of some instrument and encased in a Plexiglas cube, is not the first piece you see, nor the most prominent (nor is there any conceivable depiction of tennis). But it’s remarkable. Peering inside the theoretical diorama, the figures contain imaginative lives of their own. In referencing the environment so abstractly, Huff does a supreme job of remapping a new one.